Chemical Analyses and Formulas in Ceramics

Ceramic chemistry is cooking meets alchemy. You blend ingredients like feldspar, silica, whiting, and clay, then the kiln drives off carbon dioxide, water vapor, and other volatiles. What’s left is a glassy matrix of oxides—the building blocks that fuse on your pots. To understand or adjust how a glaze fires, we track these oxide “ingredients” with percentage analyses and formulas so we can predict whether a glaze will melt fluidly, stay matte, or fit the claybody.

In Oxides in Ceramics we looked at the major oxides—fluxes, glass-formers, and stabilizers. In Raw Materials we saw how a single material often brings several oxides to the mix. In a real recipe five or six materials might supply everything you need, and once fired it’s the overall oxide balance that matters.

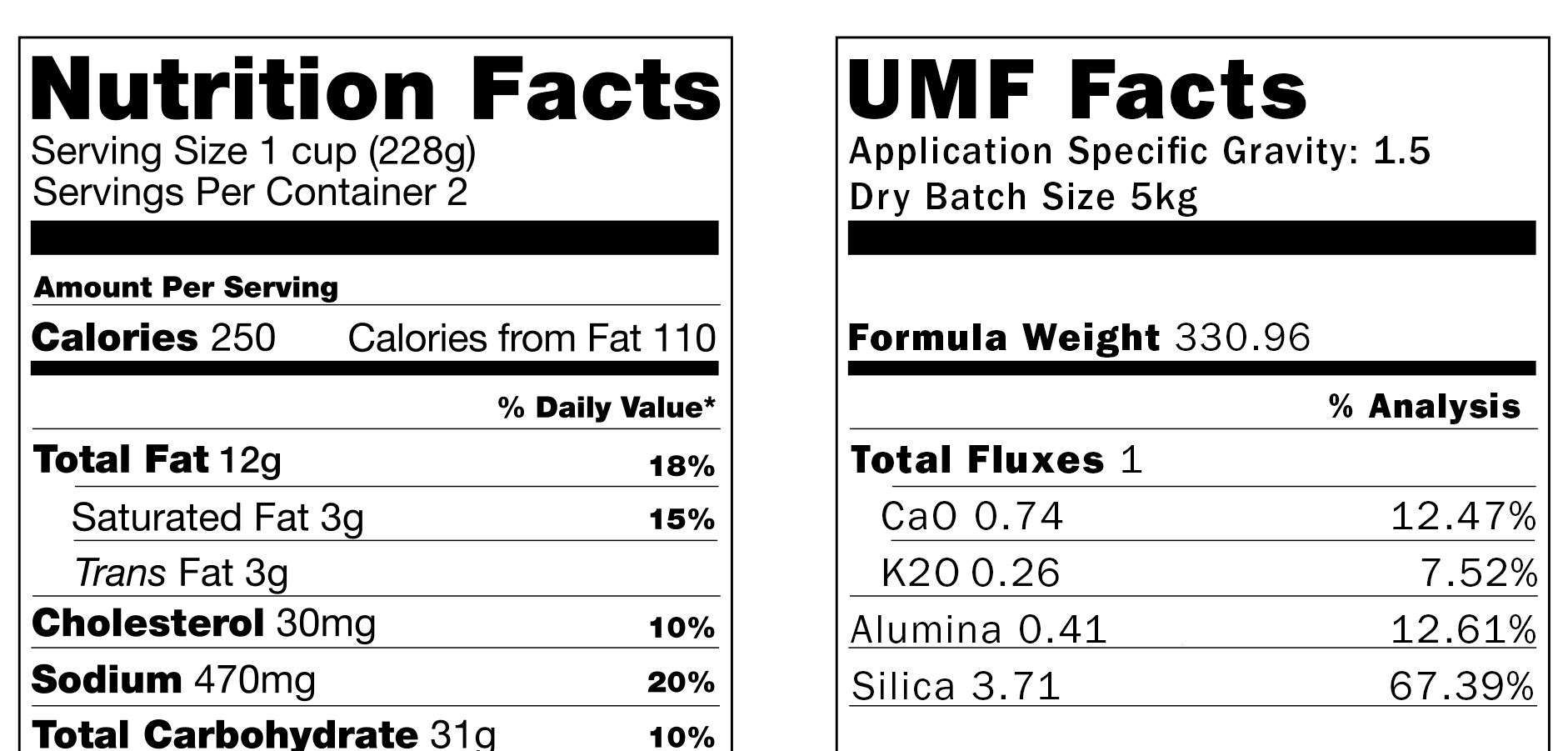

So while it’s useful to know potash feldspar’s ratio of silica to alumina to K₂O, or that whiting yields CaO, the fired glaze is a brand-new chemical analysis. Analyses tell us what the total blend looks like—your glaze’s “nutritional facts”—so you can see how much SiO₂, Al₂O₃, CaO, and other oxides end up in the result.

Percentage Analyses

A glaze analysis is similar to the nutritional information on food packaging. Both food and glazes are made up of ingredients that contribute to the overall composition.

Think of a ceramic raw material’s percent analysis like a nutrition label. Instead of protein or fat, it tells you how much SiO₂, Al₂O₃, CaO, etc., you get in 100 grams of that material. Each oxide acts a bit like a “nutrient”:

- SiO₂ (Silica) forms the main glass structure.

- Al₂O₃ (Alumina) thickens and stabilizes the melt, preventing it from becoming a runny mess.

- Fluxes like CaO, K₂O, or Na₂O lower the melting temperature.

If a potash feldspar “label” reads 64.8% SiO₂, 18.3% Al₂O₃, and 17% K₂O, that means 100 grams of feldspar gives you about 64.8 grams silica, 18.3 grams alumina, and 17 grams potash oxide (K₂O). Some materials, like whiting (calcium carbonate) , lose weight when heated (CO₂ gasses off), so part of their analysis is Loss on Ignition (LOI). Think of it like water weight cooking off: the kiln simply removes that portion.

Loss on Ignition (LOI) refers to the percentage of weight a material loses when it is heated to a high temperature and any volatile substances are burned off. In ceramics, this measurement helps to understand the presence of substances like water or carbonates in a material, which can affect the final properties of the glaze or clay body.

Example: A Simple Glaze Recipe

Consider a glaze recipe that’s measured by weight:

- 40% Potash Feldspar

- 30% Silica

- 20% Whiting

- 10% Kaolin

Each raw material can be “unpacked” into its oxide make-up. For instance:

- Potash Feldspar → mostly silica (SiO₂), alumina (Al₂O₃), and potash (K₂O).

- Whiting → mostly CaO, though it shows up chemically as CaCO₃ before firing. The CO₂ is LOI.

- Kaolin → mostly Al₂O₃ and SiO₂, plus bound water that turns into steam when fired.

Calculating Oxide Contributions

To get the full “nutritional profile,” multiply the material’s recipe percentage by that material’s oxide percentages. First, let’s look at the analyses of each material in the recipe:

Example Material Percent Analyses:

| Material | SiO₂ | Al₂O₃ | K₂O | CaO | LOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potash Feldspar | 64.8% | 18.3% | 17% | - | 0% |

| Silica | 100% | - | - | - | 0% |

| Whiting | - | - | - | 56.1% | 43.9% |

| Kaolin | 47.3% | 40.2 | - | - | 12.5% |

In the recipe, potash feldspar makes up 40% of the glaze. So, 40% of the SiO₂ in feldspar contributes to the total SiO₂ in the glaze. We calculate this as follows:

40% of the glaze × 64.8% SiO₂ in feldspar = 25.9% SiO₂

We do the same for its Al₂O₃ and K₂O, then repeat for the other ingredients. Finally, we add up each oxide from all sources:

Example Recipe Percent Analysis:

| Ingredient | Amount | SiO₂ | Al₂O₃ | K₂O | CaO | LOI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potash Feldspar | 40% | 25.9% | 7.3% | 6.8% | - | - |

| Silica | 30% | 30.0% | - | - | - | - |

| Whiting | 20% | - | - | - | 11.2% | 8.8% |

| Kaolin | 10% | 4.7% | 4.0% | - | - | 1.2% |

| Total | 100% | 60.6% | 11.3% | 6.8% | 11.2% | 10.0% |

Now we can see the total analysis: The “fired” glaze will have ~60.6% total SiO₂, ~11.3% Al₂O₃, ~6.8% K₂O, ~11.2% CaO, with the remainder being LOI or trace oxides. That final set of percentages is like a broad snapshot of your glaze’s chemistry, showing how much glass-forming silica you have relative to flux oxides like CaO or K₂O.

Since the LOI is a volatile component that burns off during firing, we can exclude it from the final analysis to get a clearer picture of the glaze’s composition:

| SiO₂ | Al₂O₃ | K₂O | CaO | LOI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Analysis | 60.6% | 11.3% | 6.8% | 11.2% | 10.0% |

| 100% Analysis (No LOI) | 67.4% | 12.6% | 7.5% | 12.5% |

Building a Formula from Percentages

While weight percentages tell us how much of each oxide there is, ceramic reactions happen on a molecular level. A glaze with 30% silica by weight doesn’t necessarily have half as many “molecules” of silica as a glaze with 60% silica, because each oxide has a different molecular weight.

In the intense heat of the kiln, raw materials decompose into oxide molecules that chemically bond to form glass. A molecular formula answers: How many molecules of each oxide are there, relative to one another? This is akin to saying, “For every 1 molecule of K₂O, how many molecules of SiO₂ do we have?”

From Weight Percent to a “Raw” Formula

Once we have the final (fired) oxide makeup in weight percent, for instance, 67.4% SiO₂, 12.6% Al₂O₃, 7.5% K₂O, and 12.5% CaO, the next step is to convert those percentages into moles. Essentially, we want to count how many molecules of each oxide are present, not just how many grams.

Grams can be misleading because some oxides are heavier than others. Counting moles lets us see how many “pieces” of each oxide we truly have.

-

List the Oxides & Their Weight Percentages Take our 100% glaze analysis example from above:

- SiO₂ 67.4%

- Al₂O₃ 12.6%

- K₂O 7.5%

- CaO 12.5%

-

Divide by Formula (Molecular) Weights Each oxide has a known formula weight, roughly how many grams per mole. For instance, SiO₂ is about 60.1 g/mol. If you divide 67.4 g of SiO₂ by 60.1 g/mol, you get ~1.12 moles. Do this for each oxide:

SiO₂ 67.4 ÷ 60.1 ≈ 1.12 moles Al₂O₃ 12.6 ÷ 102 ≈ 0.124 moles K₂O 7.5 ÷ 94.2 ≈ 0.08 moles CaO 12.5 ÷ 56.1 ≈ 0.223 molesYour “raw” formula is:

SiO₂ 1.12, Al₂O₃ 0.124, K₂O 0.08, CaO 0.223

What is Formula Weight / Molar Mass? Every oxide or compound has a chemical formula (e.g., SiO₂) made of atoms with specific atomic weights. The formula weight (also called molecular mass or molar mass) is the sum of the atomic weights in one molecule of that compound. For example, SiO₂ has 1 silicon atom (~28.1 g/mol) plus 2 oxygen atoms (2 × 16 = 32 g/mol) for a total of ~60.1 g/mol. That means 60.1 grams of SiO₂ = 1 mole (~6.022×10²³ molecules). If you have 67.4 g of SiO₂ and divide by 60.1, you get ~1.12 moles of SiO₂. See Molar mass of common formulas.

“Unifying” the Formula

After finding these raw mole counts, potters often unify the formula, that is, scale the mole amounts so that one oxide (or group of oxides) is exactly 1.0. This makes certain comparisons or calculations simpler. The choice of which oxide (or group) to unify depends on your goal:

-

Unify on a Single Oxide: For example, if you’re studying a colorant blend, you might set CoO = 1.0 to see how much NiO or Fe₂O₃ you add relative to that cobalt baseline.

-

Unify on Al₂O₃: Common when analyzing clay bodies rich in alumina, or when you want to compare everything else to a fixed alumina level.

-

Unify the Total Fluxes (UMF/Seger Formula): The classic approach in glaze chemistry. If the total of all flux oxides (Na₂O, K₂O, CaO, MgO, etc.) is set to 1.0, you can see immediately how much Al₂O₃ and SiO₂ you have relative to “standard” flux. This is known as the Seger formula or Unity Molecular Formula (UMF).

Unification is just a scaling tool. You divide each oxide’s mole value by whichever reference you choose (one flux oxide, Al₂O₃, or the sum of fluxes). The ratios among the oxides remain the same. It’s like shifting from one recipe size to another but keeping proportions intact.

Unity Molecular Formula (UMF)

In glaze chemistry, the most common strategy is to unify all fluxes to 1.0. This is the Seger or UMF approach. Here’s how it works:

1. Identify the Fluxes

Among our raw formula

SiO₂ 1.12, Al₂O₃ 0.124, **K₂O** 0.08, **CaO** 0.223the fluxes are K₂O + CaO = 0.08 + 0.223 = 0.303 total.

Which Oxides are “Fluxes”? There’s some debate about which oxides belong in the flux column versus stabilizers or glass-formers. Traditionally, UMF includes alkali oxides (Na₂O, K₂O, Li₂O) and alkaline earths (CaO, MgO, BaO, SrO, ZnO) as fluxes, while Fe₂O₃ and others might be categorized separately or left out.

On Glazy , there’s both a standard UMF view (using historical norms) and an “extended” UMF option that counts certain additional oxides (like Fe₂O₃) as fluxes under certain conditions. Different ceramic references or software may group boron, titanium, or iron differently as well. The important thing is to be consistent within your chosen system, so you can compare apples to apples.

2. Divide Every Oxide by 0.303

K₂O: 0.08 ÷ 0.303 ≈ 0.26

CaO: 0.223 ÷ 0.303 ≈ 0.74

Al₂O₃: 0.124 ÷ 0.303 ≈ 0.41

SiO₂: 1.12 ÷ 0.303 ≈ 3.70The fluxes now sum to 1.0 (0.26 K₂O + 0.74 CaO), which places Al₂O₃ at 0.41 and SiO₂ at 3.70, all relative to 1.0 flux.

We can now write the UMF formula:

| Fluxes (R₂O, RO) | Stabilizers (R₂O₃) | Glass Formers (RO₂) |

|---|---|---|

| K₂O 0.26 | Al₂O₃ 0.41 | SiO₂ 3.70 |

| CaO 0.74 |

Analogy: If you have two cookie recipes making different numbers of cookies, you can’t compare sugar-to-flour directly. By scaling each recipe to “2 dozen cookies,” you see the differences in sugar, flour, and butter at a glance. UMF does the same for glaze fluxes, making direct comparisons easy.

UMF in Action: Two Different Recipes, One Formula

A classic illustration: consider two recipes that look different but share the exact same UMF and thus behave almost identically once fired.

- Recipe 1: 40 Potash Feldspar, 30 Silica, 20 Whiting, 10 Kaolin

- Recipe 2: 36.4 Soda Feldspar, 23.2 Wollastonite, 18 Silica, 11.6 Grolleg Kaolin

Their percent analyses might look quite different:

| SiO₂ | Al₂O₃ | Na₂O | K₂O | CaO | LOI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recipe 1 | 60.6% | 11.3% | - | 6.8% | 11.2% | 10.0% |

| Recipe 2 | 67.9% | 12.7% | 4.8% | 0.2% | 12.6% | 1.6% |

But if you convert them to UMF, you’ll see that both unify to the same essential formula:

Recipe 1 UMF

R₂O/RO (Fluxes): 0.26 K₂O, 0.74 CaO

R₂O₃ (Stabilizer): 0.41 Al₂O₃

RO₂ (Glass-former): 3.71 SiO₂Recipe 2 UMF

R₂O/RO (Fluxes): 0.26 Na₂O, 0.74 CaO

R₂O₃ (Stabilizer): 0.41 Al₂O₃

RO₂ (Glass-former): 3.71 SiO₂So even though they use different raw materials (K₂O vs. Na₂O source), both end up with 1.0 total flux, 0.41 Al₂O₃, and 3.71 SiO₂. That means similar fired results: melting range, gloss, surface character, and so on.

Key Ratios in the UMF

Once you’ve converted a glaze recipe to a Unity Molecular Formula (UMF), two ratios often stand out:

- Silica:Alumina (SiO₂ : Al₂O₃)

- Flux Ratio (how the flux oxides split between “alkali” and “alkaline earth,” or how one flux compares to another)

Using our example UMF:

K₂O 0.26 CaO 0.74 | Al₂O₃ 0.41 | SiO₂ 3.70Silica:Alumina Ratio

- Calculation: 3.70 (SiO₂) ÷ 0.41 (Al₂O₃) ≈ 9.0

- Interpretation:

- A ratio of ~9 suggests a glossy melt (given adequate temperature), possibly prone to crazing if combined with high-expansion fluxes.

- Lower ratios (3–5) may be matte or underfired; moderate (5–7) is typical of many stable stoneware glazes.

Flux Ratio

- Calculation: In UMF, since total flux = 1.0, the flux values directly represent their proportions, so just add up the alkali and alkaline earth fluxes:

- Alkali (R₂O) Percentage: K₂O = 0.26 (or 26% of total flux)

- Alkaline Earth (RO) Percentage: CaO = 0.74 (or 74% of total flux)

- Flux Ratio: 26% alkali, 74% alkaline earth (On Glazy, you may see this written as

R₂O:RO 0.27 : 0.73.)

- Interpretation:

- High flux ratio (high alkali/R₂O) → strong flux, higher expansion, more fluid, but more prone to crazing.

- Low flux ratio (low alkali/R₂O, high alkaline earth/RO) → typically lower expansion, stiffer melt, can promote mattes.

- Common ratios for stable glazes range from 0.2:0.8 to 0.3:0.7, although you’re likely to see a range of ratios in practice.

Practical Tip: If you see a high flux ratio, watch for crazing. If your glaze is too stiff or low in gloss, increasing the flux ratio (i.e. adding alkali/R₂O) can help it flow better.

Traditional vs. Extended UMF

Historically, UMF calculations only included certain oxides (Na₂O, K₂O, CaO, MgO, etc.) as fluxes. Boron, iron, titanium, and colorants (e.g. CuO, CoO) often appeared in separate columns and were sometimes treated as “other”.

Traditional UMF Oxide Groupings

- R₂O Group: Na₂O, K₂O, Li₂O

- RO Group: PbO, SrO, BaO, ZnO, CaO, MgO, MnO

- R₂O₃ (Stabilizers): Al₂O₃

- B₂O₃ (Special Case)

- RO₂ (Glass-Formers): SiO₂, ZrO₂, SnO₂, TiO₂

- Other Oxides: Fe₂O₃, MnO₂, CuO, etc.

Many potters still use that approach, and that’s perfectly fine as long as you’re consistent.

Extended UMF (Colorants as Fluxes)

More recently, potters and researchers have noted that if certain colorants (like CoO, CuO) are present in higher amounts, they may function partly as fluxes. This has led to an extended or experimental UMF approach, such as the one developed by Matthew Katz and Rose Katz (Ceramic Materials Workshop). Their approach reclassifies some colorants and metallic oxides as fluxes if they significantly affect the melt.

Rose Katz’s 2019 NCECA Lecture “COLORFORMS” discusses the roles of all major colorants:

Glazy’s “Extended” UMF comes directly from Matthew & Rose Katz’s Experimental UMF Calculator. This spreadsheet calculator can be downloaded here.

Note that Extended UMF was added to Glazy a few years ago, and the CMW spreadsheet may have changed since then.

In Glazy, you can choose “Extended UMF” mode under your account settings to see colorants (e.g. CoO, CuO) re-labeled as fluxes when present above trace amounts. If you keep them “outside unity,” you won’t see their potential fluxing effect in the formula. Both methods are valid, just pick one system and interpret it consistently. See “UMF Oxide Groups Reference”

The takeaway: UMF is a model, and we refine it to suit real-world observations. Traditional UMF is enough for most daily glaze work, but if your colorants are high or you do specialized surfaces (like crystalline glazes or saturated iron glazes), an extended UMF might give clearer insights.

Calculated Thermal Expansion (CTE)

Ever noticed a mug’s glaze develop a web of fine cracks (crazing) or flake off in shards (shivering)? These are signs of thermal expansion mismatch between glaze and clay.

Calculated Thermal Expansion (CTE) is as a handy number that we can use to compare relative expansion between two analyses, e.g. when adjusting a glaze to reduce crazing we want the CTE to go down in comparison to the original glaze.

The method for calculating thermal expansion for an analysis is very simple, it is the sum of the products of each oxide amount and the coefficient of linear expansion for that oxide.

Take the famous Leach 4321 recipe:

Potash 40

Silica 30

Whiting 20

Kaolin 10Let’s further simplify the problem, replacing Potash with Pearl Ash:

Silica 44.84

Kaolin 26.76

Whiting 18.97

Pearl Ash 9.44Normalized to 100% (removing LOI), the percent weight analysis for this recipe is:

SiO₂ 67.390, Al₂O₃ 12.612, K2O 7.524, CaO 12.474

The West & Gerrow coefficients used by Digitalfire are:

SiO₂ 0.035, Al₂O₃ 0.063, K2O 0.331, CaO 0.148

The calculation is then:

SiO₂ 67.390 * 0.035 = 2.359

Al₂O₃ 12.612 * 0.063 = 0.795

K2O 7.524 * 0.331 = 2.49

CaO 12.474 * 0.148 = 1.846Adding those results: Calculated thermal Expansion: 7.49

Practical Adjustments - To reduce crazing: swap out high-expansion fluxes (Na₂O, K₂O) for lower-expansion ones (MgO, ZnO), or add more SiO₂. - To reduce shivering: do the opposite: increase expansion by using more alkali flux or reducing silica.

Using the Pearl Ash 4321, let’s swap K2O for Na2O:

Leach 4321 Soda Ash:

Silica: 45.29

Kaolin: 27.03

Whiting: 19.16

Soda Ash: 8.53These recipes have equivalent UMF formulas, except K2O has been swapped for Na2O:

Pearl Ash 4321: 0.264 K2O, 0.736 CaO, 0.409 Al₂O₃, 3.71 SiO₂

Soda Ash 4321: 0.264 Na2O, 0.736 CaO, 0.409 Al₂O₃, 3.71 SiO₂

But of course the weight % analyses differ (normalized to 100% without LOI):

Pearl Ash 4321: SiO₂ 67.39, Al₂O₃ 12.612, K2O 7.524, CaO 12.474

Soda Ash 4321: SiO₂ 69.171, Al₂O₃ 12.946, Na2O 5.08, CaO 12.803

The calculated expansion for Soda Ash 4321:

SiO₂ 69.171 * 0.035 = 2.42

Al₂O₃ 12.946 * 0.063 = 0.816

Na2O 5.08 * 0.387 = 1.966

CaO 12.803 * 0.148 = 1.895Adding those results: Calculated thermal Expansion: 7.10

To summarize, for two UMF-equivalent analyses swapping K2O for Na2O, the K2O version has a higher calculated expansion than the Na2O version, even though the oxide Na2O has a higher coefficient of expansion. This problem arises from the fact that we are specifying “equivalence” in the UMF system but using weight % analyses to calculate expansion.

Conclusion

We’ve seen how to move from weight percentages to molecular formulas, and then to a Unity Molecular Formula (UMF). Once you master these steps, you gain a powerful way to predict, compare, and fine-tune glazes, bridging technique and theory.

Why the UMF Is Powerful:

-

Apples-to-Apples Comparison Two glaze recipes might look totally different in raw materials yet share the same UMF. If so, they’ll likely fire with similar melt behavior, an invaluable insight when swapping out ingredients.

-

Guidance from Limit Formulas UMF-based limit formulas set target “windows” for Al₂O₃ and SiO₂ at various cone ranges. If your UMF drifts far outside those windows (say extremely high silica or lots of alkali flux),expect issues like crazing, running, or underfired surfaces.

-

Instant Clarity on Key Ratios The UMF pinpoints your silica:alumina ratio (e.g., gloss vs. matte) and your flux ratio. Identifying these ratios quickly flags potential high-expansion glazes or stiff melts.

-

Pinpointing & Solving Defects Is the glaze running off the pot? Maybe UMF shows too little Al₂O₃. Is it crazing? Possibly the flux portion is heavy in sodium/potassium. By altering one oxide in unity form, you see exactly how it reshapes the chemistry.

-

Straightforward Substitution Once you know the UMF, you can swap flux sources (whiting for dolomite, for example) without changing the overall formula. That keeps the glaze’s core behavior intact while experimenting with specific material characteristics.

-

Supporting Iteration & Creativity Whether you want a crystal glaze or a satin-matte, the UMF approach lays out how to shift fluxes, silica, or alumina to move in that direction. Over time, you’ll develop a sense of which UMF “zones” yield your desired surface.

-

A Flexible (Not Perfect) Model Some sources categorize boron or iron differently; real materials contain impurities. UMF is still a model, not absolute chemistry. But it remains widely adopted because it systematically shows what a glaze is made of and how to adjust it.

Materials vary, and their chemical analyses may be somewhat inaccurate, so your formula is always an approximation. Still, it often gets you remarkably close. Keep experimenting, keep refining, and let your test firings confirm your adjustments.

Sources & Further Reading

- UMF Oxide Groups Reference

- Linda Arbuckle, “Introduction to Glaze Calculation ”

- David Hewitt Pottery: Calculating Crazing : Table 2 contains Coefficients of Thermal Expansion that the West & Gerrow values from “Ceramic Science for the Potter” used by Digitalfire. West & Gerrow has coefficients in terms of both ”% Wt. Linear” and “Unity Mol. Coeff. Linear”

- John Sankey: Glaze Thermal Expansion also contains a list (“Comparison of expansion data”). The “by weight” values all have Na2O > K2O, but Sankey’s own “molar” values have K2O > Na2O.

- Digitalfire: Calculated Thermal Expansion

- Ceramic Materials Workshop’s UMF Calculator for Extended UMF

- Dave Finkelnburg, “How Glazes Melt” (NCECA 2012)

- Clay and glazes for the potter by Daniel Rhodes

- The ceramic spectrum by Robin Hopper