Material Substitution in Ceramic Recipes

It happens all the time: you find a great glaze on Glazy but you’re missing a material, or you’re translating a recipe from another country and don’t recognize the ingredient names. As long as you have materials with similar oxides, you can make substitutions and still get great results. This guide shows you how.

Examples of common cooking substitutions. Material substitutions in ceramics is a bit more complex, but the same principles apply.

When you’re missing a raw material or you want to tweak a glaze or clay body, material substitution comes into play. Like swapping honey for sugar, ceramic substitutions aren’t always one-to-one. Each material brings its own mix of oxides, which affect melting temperature, surface finish, color, and more. Understanding those oxide makeups lets you recreate glazes from other regions or reverse-engineer older glazes that used hard-to-find ingredients.

From the moment potters started sharing glaze recipes, we’ve wrestled with the fact that not all raw materials are equally available worldwide. (In fact, one of the first cases of industrial espionage involved smuggling the secrets of porcelain from China to Europe!) Put another way, “glazes don’t travel well”. A feldspar from South America might not be identical to a feldspar mined in Europe or Asia, but both can still supply the same base oxides: potassium, sodium, alumina, silica, etc. By focusing on the oxide composition rather than brand names or local trade names, you can:

- Substitute unavailable or discontinued raw materials (like Gerstley Borate) with equivalents (such as boron frits or borax). EPK and Custer no longer available? Use whatever kaolin and potash feldspar you have on hand, instead.

- Recreate glazes from any part of the world. Someone in another part of the world posted a beautiful recipe, and you can’t even read the ingredients. No problem! As long as you know the oxide breakdown, you can match it with your local materials.

- Reverse-engineer historical or ancient recipes by matching the published chemical analysis with your local materials.

Important: Always mix small test batches and do a test firing before committing to a large batch. Material analyses vary by supplier, and even small changes can drastically shift color or surface quality. Substitutions might look good on paper but behave differently in the kiln.

Basic One-to-One Substitutions

In some cases, the material swap is straightforward because you only need to replace one main oxide, for instance, substituting cobalt carbonate for cobalt oxide to color a glaze blue.

Calculating Substitutions

When you replace one raw material with another, you want the same amount of the key oxide (e.g., CoO for cobalt color, CaO for a calcium flux) so your glaze behaves similarly. Each compound has a certain percentage of that oxide. So if “Material A” contains more of the target oxide per gram than “Material B,” you’ll need less of Material A to get the same oxide, or more of Material B.

There are two common ways to figure this out:

- Using Mass Percent (“Percentage Analysis”). Many suppliers list the oxide content of their materials, e.g., “Cobalt Carbonate is 63% CoO.” That means for every 100 g of cobalt carbonate, ~63 g are actual CoO.

- Using Molecular Weights (Molar Mass). You can also start from the material’s chemical formula (like Co₃O₄) and sum the atomic weights to see what fraction is cobalt or CoO. This yields the same ratio, just a different route to get there.

Just as ingredients in the kitchen have nutritional facts, ceramic materials have oxide analyses that can be used to calculate substitutions.

Example: Cobalt Oxide ↔ Cobalt Carbonate

Mass Percent (Percentage Analysis) Approach

- Cobalt Oxide is often Co₃O₄, and actually contains only ~93% CoO by weight.

- Cobalt Carbonate is ~63% CoO by weight (the rest is CO₂ that burns off, plus minor impurities).

If your recipe calls for 1 g of cobalt oxide (~93% CoO), but you only have cobalt carbonate (~63% CoO):

Ratio = (CoO% in oxide) / (CoO% in carbonate)

= 93 / 63

≈ 1.48- So to replace 1 g of cobalt oxide, you need about 1.48 g of cobalt carbonate.

Conversely:

Ratio = (CoO% in carbonate) / (CoO% in oxide)

= 63 / 93

≈ 0.68- To replace 1 g of cobalt carbonate with oxide, multiply by 0.68.

Molecular Weight (Molar Mass) Approach

If you only had the chemical formulas:

- Cobalt Oxide is often Co₃O₄. Adding up atomic weights, you’d find ~73.4% of it is cobalt metal, which corresponds to ~93% CoO overall.

- Cobalt Carbonate (CoCO₃) breaks down to ~49.5% cobalt metal, or about 63% CoO.

Either way, you end up with the same ratio ≈ 1.48 when substituting one for the other, because cobalt oxide has a higher percentage of “usable cobalt oxide” per gram.

Example: Whiting (CaCO₃) ↔ Wollastonite (CaSiO₃)

- Whiting (Calcium Carbonate, CaCO₃) is ~56.1% CaO, ~43.9% CO₂.

- Wollastonite (Calcium Silicate, CaSiO₃) is ~48.3% CaO, ~51.7% SiO₂, with no CO₂ to burn off.

Calculation Example If a glaze recipe calls for 10% whiting, that translates to 10% × 0.561 = 5.61% CaO in the glaze. To get the same CaO from wollastonite (48.3% CaO):

Required Wollastonite = 5.61% CaO / 0.483

≈ 11.6%But now wollastonite also brings ~51.7% SiO₂:

Extra silica = 11.6% × 0.517

≈ 6%So if your glaze already includes silica (flint), you can reduce it by ~6% to keep total SiO₂ the same.

Example: Barium Carbonate ↔ Strontium Carbonate

Here we match moles of the alkaline earth oxides (BaO vs. SrO). They’re not identical, but if you’re replacing BaCO₃ with SrCO₃ for safety (strontium is less toxic), you want the same total moles of flux.

- Barium Carbonate (BaCO₃) is ~77.5% BaO by weight.

- Strontium Carbonate (SrCO₃) is ~70% SrO by weight.

If a glaze uses 10 g BaCO₃ (7.75 g BaO), you need enough SrCO₃ to get 7.75 g SrO:

7.75 / 0.70 ≈ 11.07 gExample in a Real Glaze

Original Glaze:

Leach 4321 +1% Cobalt Oxide

40 Feldspar

30 Silica

20 Whiting

10 Kaolin

+1% Cobalt OxideIf you only have cobalt carbonate:

- Oxide is 93% CoO vs. carbonate at 63% CoO → ratio = 93 ÷ 63 ≈ 1.48.

- So 1% cobalt oxide → 1.48% cobalt carbonate.

Revised Glaze:

40 Feldspar

30 Silica

20 Whiting

10 Kaolin

+1.48% Cobalt CarbonateNow you’ve matched the same amount of CoO. This new recipe should look very similar to the original, but always test to fine-tune.

Re-creation of Historical Glazes

Note: In the following section we’ll learn how to use Nigel Wood’s “Percentage Method” to create recipes from analyses of historical glazes. You might not be interested in antiques! But once you learn the technique, you’ll be able to apply it to material substitutions in general, from replacing a complex material like Gerstley Borate to re-creating a recipe from a different country.

Some of the most fascinating substitutions involve resurrecting recipes from centuries past. By analyzing the oxide composition of historical shards or published data, modern potters can replicate glazes that once relied on region-specific or long-lost materials.

-

Obtain or Reference a Chemical Analysis Books like Nigel Wood’s Chinese Glazes detail ancient formulas and their oxide breakdowns. Archaeological or scientific papers often publish XRF (X-ray fluorescence) analyses of historical pieces.

-

Convert the Analysis into a Recipe Translate the oxide percentages into a modern recipe using available materials: local feldspars, whiting (or limestone), kaolin, wood ash, etc. The goal is to mimic the original ratio of flux (Na₂O, K₂O, CaO, MgO), stabilizer (Al₂O₃), and glass-former (SiO₂).

-

Use Glaze Software for Precision Input your target analysis (e.g., 65% SiO₂, 15% Al₂O₃, 10% CaO, 10% KNaO fluxes, plus trace Fe₂O₃). Then experiment with combinations of modern raw materials until you match that oxide profile. You can use Glazy’s Target & Solve to automatically calculate the recipe for you.

-

Fire and Adjust Historical kilns often had different firing atmospheres (wood, reduction, etc.), temperatures, and firing & cooling profiles. Recreating these conditions can be essential, especially for sensitive glazes like copper reds. Fire test tiles, compare results, and tweak the recipe if needed.

Nigel Wood’s “Percentage Method”

Even though Song Dynasty celadons were made from traditional Chinese materials (glaze stone and glaze ash), we can re-create the same glazes using our own modern materials. In Chinese Glazes, Nigel Wood shows how to derive a usable recipe from a target oxide analysis, without relying on glaze software. Here’s the core idea:

Note that we’ll be referring to KNaO a lot in these examples. KNaO is the sum of K₂O and Na₂O, which are often combined in analyses because they behave fairly similarly in glazes and simplify the problem of substitution.

-

List Your Target Oxides Write down the oxide composition you want to match, for example, 66% SiO₂, 15% Al₂O₃, 11% CaO, 5% KNaO (K₂O + Na₂O combined), etc.

-

Pick Your Raw Materials Choose which modern materials will provide each oxide. Complex materials (like feldspar) typically supply multiple oxides at once (SiO₂, Al₂O₃, KNaO). Simpler materials (like pure silica or whiting) provide just one main oxide.

-

Start with the Most Complex Material

- Identify which oxide in that material you specifically need (e.g., KNaO in feldspar).

- Calculate “parts”: How many parts of that material you need to supply the target oxide. Calculation is

Parts = (Target oxide %) / (Oxide % in raw material) × 100. - Multiply the raw material’s other oxides by this decimal fraction. Subtract those from your list of target oxides, whatever is left still needs to be supplied by other materials.

-

Move to the Next Oxide

- Pick the next most complex material or the next biggest oxide you still need.

- Repeat the same “parts” calculation for that oxide, subtract its associated oxides from the target, and see what remains.

-

Top Off with Simpler Materials Once you’ve handled the main fluxes (like KNaO, CaO, MgO) and alumina (Al₂O₃), use single-oxide sources (pure silica, whiting, iron oxide, etc.) to supply whatever is left.

-

Sum and (Optionally) Normalize

- After you’ve accounted for all oxides, you’ll have a list of “parts” for each raw material.

- You can either use them as-is or convert to 100% by adding all parts together, then dividing each part by that total × 100.

-

Test! Even if the math is perfect, slight variations in actual material composition, kiln atmosphere, and firing schedule can lead to differences. Always run small test batches first.

This step-by-step approach (subtracting the oxide amounts as you go) can re-create a specific ancient glaze chemistry reliably. While a bit more manual than modern glaze apps, it’s straightforward once you get the hang of it.

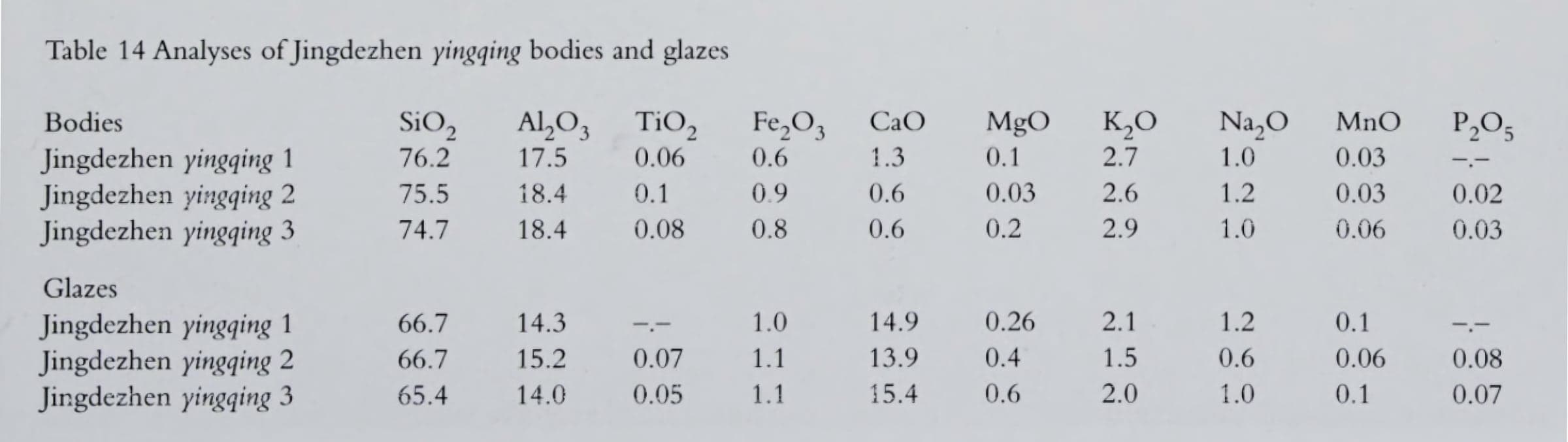

Some of the historical analyses in Nigel Wood’s Chinese Glazes.

“Percentage Method” Practical Example

Let’s re-create an ancient glaze using an analysis from Nigel Wood’s Chinese Glazes:

| SiO₂ | Al₂O₃ | TiO₂ | Fe₂O₃ | CaO | MgO | (KNaO) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue Celadon Analysis | 66.33 | 14.28 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 11.34 | 1.17 | 5.29 |

Let’s pick some common materials to fulfill each oxide in the analysis. Also, let’s list our ingredients in order of complexity (i.e., how many oxides they contain):

- KNaO: Potash Feldspar (64.76% SiO₂, 18.32% Al₂O₃, 16.92% K2O (aka KNaO))

- Al₂O₃: Kaolin (47.29% SiO₂, 40.21% Al₂O₃, 12.5% LOI)

- MgO: Dolomite (30.48% CaO, 21.91% MgO, 47.61% LOI)

- CaO: Whiting (56.1% CaO, 43.9% LOI)

- SiO₂: Silica (100% SiO₂)

- Fe₂O₃: Red Iron Oxide (95% Fe₂O₃, 5% LOI)

For this example we use simpler “theoretical” materials, but in practice it’s best to use real-world materials like Custer or Mahavir feldspar instead of the generic “Potash Feldspar”.

Now let’s start with the most complex material, Potash Feldspar, and work our way down:

- We need 5.29% total KNaO, and our potash feldspar has 16.92% KNaO as K2O. So we need

(5.29 ÷ 16.92) × 100 ≈ 31.27 parts potash feldspar.- 31.27 parts potash feldspar × 16.92% KNaO = 5.29% KNaO.

- 31.27 parts potash feldspar × 64.76 SiO₂ = 20.25% SiO₂.

- 31.27 parts potash feldspar × 18.32 Al₂O₃ = 5.10% Al₂O₃.

| Parts | SiO₂ | Al₂O₃ | TiO₂ | Fe₂O₃ | CaO | MgO | (KNaO) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue Celadon Analysis | 66.33 | 14.28 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 11.34 | 1.17 | 5.29 | |

| Potash Feldspar | 31.27 | 20.25 | 5.73 | 5.29 | ||||

| To be found: | 46.1 | 8.55 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 11.34 | 1.17 | X |

The remaining analysis is then: 46.1% SiO₂, 8.55% Al₂O₃, 0.03 TiO₂, 1.0% Fe₂O₃, 11.34% CaO, and 1.17% MgO.

Now let’s source the remaining alumina from Kaolin (47.29% SiO₂, 40.21% Al₂O₃, 12.5% LOI):

- We need 8.55% Al₂O₃, and our kaolin has 40.21% Al₂O₃. So we need

(8.55 ÷ 40.21) × 100 ≈ 21.3 parts kaolin.- 21.3 parts kaolin × 40.21% Al₂O₃ = 8.55% Al₂O₃.

- 21.3 parts kaolin × 47.29% SiO₂ = 10.1% SiO₂.

| Parts | SiO₂ | Al₂O₃ | TiO₂ | Fe₂O₃ | CaO | MgO | (KNaO) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue Celadon Analysis | 66.33 | 14.28 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 11.34 | 1.17 | 5.29 | |

| Potash Feldspar | 31.27 | 20.25 | 5.73 | 5.29 | ||||

| To be found: | 46.1 | 8.55 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 11.34 | 1.17 | X | |

| Kaolin | 21.3 | 10.1 | 8.55 | |||||

| To be found: | 36 | X | 0.03 | 1.0 | 11.34 | 1.17 |

After adding Kaolin, the remaining analysis is: 36% SiO₂, 0.03% TiO₂, 1.0% Fe₂O₃, 11.34% CaO, and 1.17% MgO.

Now let’s source the MgO from Dolomite, which contains both MgO and CaO (21.91% MgO, 30.48% CaO, 47.610 LOI):

- We need 1.17% MgO, and Dolomite has 21.91% MgO. So we need

(1.17 ÷ 21.91) × 100 ≈ 5.34 parts dolomite.- 5.34 parts dolomite × 21.91% MgO = 1.17% MgO.

- 5.34 parts dolomite × 30.48% CaO = 1.63% CaO.

| Parts | SiO₂ | Al₂O₃ | TiO₂ | Fe₂O₃ | CaO | MgO | (KNaO) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue Celadon Analysis | 66.33 | 14.28 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 11.34 | 1.17 | 5.29 | |

| Potash Feldspar | 31.27 | 20.25 | 5.73 | 5.29 | ||||

| To be found: | 46.1 | 8.55 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 11.34 | 1.17 | X | |

| Kaolin | 21.3 | 10.1 | 8.55 | |||||

| To be found: | 36 | X | 0.03 | 1.0 | 11.34 | 1.17 | ||

| Dolomite | 5.34 | 1.63 | 1.17 | |||||

| To be found: | 36 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 9.71 | X |

After adding Dolomite, the final analysis is: 36% SiO₂, 0.03% TiO₂, 1.0% Fe₂O₃, 9.71% CaO.

Our remaining oxides can all be fulfilled by simpler, single-oxide materials, which simplifies the final calculations.

Let’s source the remaining CaO with Whiting (56.1% CaO, 43.9% LOI), SiO₂ with Silica (100% SiO₂), and Fe₂O₃ with Red Iron Oxide (95% Fe₂O₃, 5% LOI):

- We need 9.71% CaO, and Whiting has 56.1% CaO. So we need

(9.71 ÷ 56.1) × 100 ≈ 17.3 parts whiting.- 17.3 parts whiting × 56.1% CaO = 9.71% CaO.

- We need 36% SiO₂, and Silica has 100% SiO₂. So we need

(36.0 ÷ 100) × 100 = 36.0 parts silica.- 36.0 parts silica × 100% SiO₂ = 36% SiO₂.

- We need 1% Fe₂O₃, and Red Iron Oxide has 95% Fe₂O₃. So we need

(1 ÷ 95) × 100 ≈ 1.05 parts red iron oxide.- 1.05 parts red iron oxide × 95% Fe₂O₃ = 1% Fe₂O₃.

| Parts | SiO₂ | Al₂O₃ | TiO₂ | Fe₂O₃ | CaO | MgO | (KNaO) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue Celadon Analysis | 66.33 | 14.28 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 11.34 | 1.17 | 5.29 | |

| Potash Feldspar | 31.27 | 20.25 | 5.73 | 5.29 | ||||

| To be found: | 46.1 | 8.55 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 11.34 | 1.17 | X | |

| Kaolin | 21.3 | 10.1 | 8.55 | |||||

| To be found: | 36 | X | 0.03 | 1.0 | 11.34 | 1.17 | ||

| Dolomite | 5.34 | 1.63 | 1.17 | |||||

| To be found: | 36 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 9.71 | X | |||

| Whiting | 17.3 | 9.71 | ||||||

| To be found: | 0.03 | 1.0 | X | |||||

| Silica | 36.0 | 36 | 0.03 | 1.0 | ||||

| To be found: | X | 0.03 | 1.0 | |||||

| Red Iron Oxide | 1.05 | 1 | ||||||

| To be found: | 0.03 | X |

We won’t bother fulfilling the small amount of TiO₂. If we did fulfill TiO₂ by using Titanium Dioxide, we’d need 0.03 parts of it. But that addition might modify the final glaze color somewhat, tinting our blue celadon slightly into green.

The final recipe ordered by amount is:

Blue Celadon Recipe:

| Material | % Amount |

|---|---|

| Silica | 36.0 |

| Potash Feldspar | 31.27 |

| Kaolin | 21.3 |

| Whiting | 17.3 |

| Dolomite | 5.34 |

| Red Iron Oxide | 1.05 |

| Total | 112.26 |

Note that it adds up to 112.26%. You can normalize the recipe to 100% by dividing each part by 112.26 and multiplying by 100:

Blue Celadon Recipe:

| Material | % Amount |

|---|---|

| Silica | 32.1 |

| Potash Feldspar | 27.85 |

| Kaolin | 19.0 |

| Whiting | 15.4 |

| Dolomite | 4.75 |

| Red Iron Oxide | 0.9 |

| Total | 100 |

Some historical kilns used wood firing and long reduction soaks, which play a huge role in the glaze’s final color and surface. Even with a perfect oxide match, modern firing differences can produce subtle variations. Always test!

Use “Target & Solve” to Re-create Ancient Glazes

The “Percentage Method” technique works well for many cases, but it can be time-consuming and error-prone. And sometimes you might get part-way through a calculation only to realize you need to adjust a previous step, or that your chosen materials can’t be used to find a solution.

Glazy’s Target & Solve can automate the process, ensuring you get the right recipe the first time.

Multi-Oxide Substitutions

If a single raw material in your glaze is missing from your studio supply, and that material contributes multiple oxides (like Gerstley Borate or a feldspar), you can’t just plug in a one-to-one substitute. Instead, remove that hard-to-get material from the recipe entirely and re-construct the glaze with ingredients that you do have. The guiding principle is simple:

-

Start from the Glaze’s Overall Analysis. If your goal is to replicate a glaze’s chemistry, either from a known formula or a published oxide breakdown, treat that as your target (e.g., “I need 5% KNaO, 11% CaO, 15% Al₂O₃, 65% SiO₂, etc.”).

-

Apply Nigel Wood’s Percentage Method (or Glazy’s Target & Solve). Choose alternate materials that, in combination, supply the same set of oxides the missing raw material was providing, and make sure the rest of the glaze’s oxides stay consistent with the target.

-

Calculate the New Recipe.

- If Gerstley Borate was a major source of B₂O₃, CaO, and Na₂O, decide how much boron frit and, say, kaolin or dolomite you need to yield an equivalent overall B₂O₃–CaO–Na₂O–Al₂O₃ balance.

- If a particular feldspar is gone, use enough of your local feldspar until the KNaO (K₂O + Na₂O) is fulfilled, then add kaolin or silica to balance out Al₂O₃ and SiO₂.

- Keep subtracting the oxide “amounts” from your target as you assign them to each local material, following the same step-by-step logic in Nigel Wood’s method.

-

Test Fire & Adjust. Even a mathematically perfect replacement can behave a bit differently in the kiln. Fire a test before making larger batches.

Substitutions Across Regions

When a glaze is published in another region (or another era) with materials you can’t get, the same principle applies: construct a whole new recipe from the same oxide analysis. Forget brand names or local trade names; as long as you know the oxide breakdown, you can find a local combination of feldspars, clays, carbonates, and frits to match it.

-

Obtain the Glaze’s original Oxide Analysis. This might be printed in a reference book or posted on Glazy.

-

Pick Your Local Materials. Suppose the recipe references “XYZ Feldspar,” but you only have Custer Feldspar available. Also note any missing raw materials like “ABC Kaolin” or “Rutile #3” that you need to replace with your local equivalents. Make sure your local materials fulfill all of the oxides in the original analysis.

-

Use Nigel Wood’s Steps (or Glazy’s Target & Solve).

- Identify each oxide you need (K₂O, Na₂O, CaO, MgO, Al₂O₃, SiO₂, B₂O₃…).

- Assign them from your local materials, subtracting as you go until you reach the target oxide totals.

- If your local feldspar has more K₂O than the original, you’ll add less potash or reduce other fluxes. If it has less silica, you add a bit more flint.

-

Test, Document, Adjust. Even if the numbers line up, differences in raw-material impurities and kiln atmosphere can shift surface or color. Keep track of each variant until you hone in on the best match.

When to Use Glazy’s Target & Solve

Nigel Wood’s manual approach works well for multi-oxide substitutions, but it is time-consuming, error prone, and you may sometimes hit a road-block where no solution is possible. Instead, you can speed up the process with Glazy’s Target & Solve. Enter the oxide profile you want, choose potential substitute materials, and let the system calculate the “parts” of each. This is especially useful when dealing with many fluxes at once or combining multiple local materials to match a single imported raw material.

Practical Tips, Testing, and Troubleshooting

By focusing on oxide composition and using systematic methods (Nigel Wood’s or Glazy’s Target & Solve), you can successfully swap or replicate materials, whether you’re substituting Gerstley Borate in a local studio or recreating a centuries-old glaze formula from the other side of the globe.

- Always run test tiles. Perfect on-paper calculations may not reflect the nuances of your kiln or local material impurities.

- Document everything. Note the exact brand and batch of materials, firing schedule, and final results. Substitutions can fail if you aren’t consistent with record-keeping.

- Adjust for multiple oxides. When you add a new frit or feldspar, you might accidentally increase silica or certain fluxes. Rebalance your recipe to maintain the same overall chemistry.

- Color response can change. Substituting fluxes (like barium with strontium) and other materials can subtly shift glaze color, surface, and other properties. Test tiles are crucial to verify final appearance.

Common Material Substitutions

Below is a quick-reference table for common one-to-one oxide swaps. Each line shows two directions (e.g., “Material A → Material B” and “Material B → Material A”) with approximate ratios. The notes column provides extra steps (like adjusting silica). For multi-oxide materials, use Glazy’s Target & Solve or the percentage method for more precise balancing.

| Swap | Ratio (Approx.) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cobalt Oxide (Co₃O₄) ↔ Cobalt Carbonate (CoCO₃) | Co₃O₄ → CoCO₃: 1 : 1.48 CoCO₃ → Co₃O₄: 1 : 0.68 | Co₃O₄ is ~93% CoO; CoCO₃ ~63% CoO. Multiply recipe amounts accordingly. E.g., 1 g oxide → 1.48 g carbonate. Carbonate releases CO₂. |

| Copper Oxide (CuO) ↔ Copper Carbonate (CuCO₃) | CuO → CuCO₃: 1 : 1.55 CuCO₃ → CuO: 1 : 0.64 | CuO is ~100% CuO; CuCO₃ ~64-65% CuO. E.g., 10 g copper oxide → ~15.5 g copper carbonate. Carbonate releases CO₂. |

| Red Iron Oxide (Fe₂O₃) ↔ Yellow Iron Oxide (Fe₂O₃∙H₂O) | Yellow → Red: 1 : 0.93 Red → Yellow: 1 : 1.08 | Reported analyses: Yellow ~88% Fe₂O₃, Red ~95%. Adjust as needed. Practical difference is small; always test-fire for color. |

| Manganese Dioxide (MnO₂) ↔ Manganese Carbonate (MnCO₃) | MnO₂ → MnCO₃: 1 : ~1.62 MnCO₃ → MnO₂: 1 : ~0.62 | MnO₂ is ~100% MnO (effective). MnCO₃ is ~61-62% MnO. E.g., 10 g MnO₂ → ~16.2 g MnCO₃. Carbonate releases CO₂. |

| Whiting (Calcium Carbonate, CaCO₃) ↔ Wollastonite (Calcium Silicate, CaSiO₃) | CaCO₃ → CaSiO₃: 1 : ~1.16 CaSiO₃ → CaCO₃: 1 : ~0.86 | Whiting is ~56% CaO, Wollastonite ~48% CaO + 52% SiO₂. Adjust silica if needed, wollastonite adds extra SiO₂. |

| Barium Carbonate (BaCO₃) ↔ Strontium Carbonate (SrCO₃) | BaCO₃ → SrCO₃: 1 : ~0.75 SrCO₃ → BaCO₃: 1 : ~1.33 | BaCO₃ ~77.5% BaO; SrCO₃ ~70% SrO. Sr is safer (less toxic). Substitutions may alter color response. Always do test tiles. |

| Kaolin ↔ Calcined Kaolin | Usually ~1 : 0.9** (calcined has no bound water) | Calcined kaolin has less “plastic” behavior; used to reduce shrinkage in glazes. Typically you reduce the weight slightly if swapping raw kaolin with fully calcined. |