What Is Clay?

Clay deposit Wikipedia, Siim Sepp

Clay is a fine-grained soil or earth material that becomes soft and moldable when wet and then permanently hardens when heated. Geologically, clay forms over long periods as rocks weather and break down into microscopic mineral particles like kaolinite. Clay found at the original rock site is primary clay (often coarser and less workable), while clay that has been moved and deposited elsewhere is secondary clay (finer, more uniform & plastic).

A key property of clay is plasticity: Its capacity to be shaped and hold a form without cracking. Under a microscope, clay particles resemble tiny flat plates. When wet, they slide smoothly over each other (imagine shuffling a deck of playing cards), which is what makes clay so flexible for shaping. As clay dries and is then fired, it shrinks and undergoes a permanent chemical change: the water in the clay is driven off, and at higher temperatures the mineral particles begin to fuse together. If you heat clay hot enough, it vitrifies (becomes glass-like and non-porous), transforming from something soft and fragile to a hard ceramic material.

Types of Clay

In ceramics, there are three broad categories of clay you’ll often hear about: earthenware, stoneware, and porcelain. Each type has different firing temperatures, different levels of impurities, and distinct working properties.

Earthenware

Examples of historical earthenware: Left: Terracotta chariot krater, ca. 1300–1230 BCE , Right: Earthenware Jug designed by Christopher Dresser, ca. 1872–75 .

Examples of contemporary terracotta, left to right: Sculpture by Douglas Baldwin Dish by Linda Arbuckle Teapot by Richard Notkin

Earthenware is typically fired at low temperatures (around 900°C–1,150°C, or 1,650–2,100°F, roughly Cone 08–02) and contains iron and other minerals that give it a warm, often reddish-brown appearance before and after firing. Because it remains slightly porous, it’s common to apply glaze when you want to make the piece watertight (think of terracotta garden pots and how they’re naturally absorbent). Earthenware is widely admired for its workability, so beginners often find it forgiving and easy to shape, although it can’t withstand the higher temperatures that stoneware or porcelain demand. Pushing it beyond its recommended firing range may cause warping or even melting.

Stoneware

Examples of historical stoneware: Left: Jar, China, late 6th century Center: Freshwater Jar, Japan, late 16th century Right: Jug, German, 17th century

Examples of contemporary stoneware, left to right: Moon Jar, Akiko Hirai Stoneware charger, Lisa Hammond Large Bizen Tsubo, Jeff Shapiro

Stoneware is a versatile clay that’s popular for functional ware and other items that need to endure regular use. It becomes non-porous and very durable at its maturing temperature in the mid- to high-fire range from Cone 5–10. Stoneware’s raw color often looks gray or brown, but it fires to a spectrum of buff, tan, gray, or deeper brown shades. Most commercial and studio stoneware bodies are blends of different clays (like ball clay for plasticity and fire clay for strength), sometimes with added sand or grog to improve workability and reduce shrinkage.

Porcelain

Examples of historical porcelain: Left: Jar with dragon, China, early 15th century Center: Bottle cooler, Jean-Claude Duplessis, 1754 Right: Teacup, designed 2012 by Nendo, Tokyo (2002–present)

Examples of contemporary porcelain, from left to right: Sculpture by Katō Tsubusa , Vessel by Takeshi Yasuda , Vase by Fukumoto Fuku

Porcelain is generally fired at higher temperatures of Cone 9-11 (approximately 1,280°C-1,320°C or 2,340°F-2,410°F). It’s composed largely of kaolin, a very pure, white clay. This purity results in its distinctive whiteness and the possibility of translucence when the piece is thin and fully vitrified. Porcelain is prized for its smooth surface and strength after firing, although its lower plasticity compared to other clays can make throwing and shaping more challenging. Porcelain is somewhat more prone to warping and cracking if not managed carefully.

Natural vs. Processed Clay

Historically, potters dug raw clay directly from the ground and removed debris like stones and roots before aging, slaking, and levigating it in water. While this can be a rewarding process, it’s labor-intensive and the quality or consistency of raw clay can vary widely even within a single deposit.

These days, most ceramicists use commercially processed clay bodies. Suppliers blend and sieve raw materials to control plasticity, shrinkage, and color. As a beginner, starting with a commercially prepared clay body saves time and reduces unpredictable results. As you gain experience, you may want to experiment with blending your own clay bodies or adding grog, sand, or other additives to tailor the clay to your needs.

Clay levigation process: Fine clay particles suspended in water while coarser sediments settle to the bottom. Image from the Art History Glossary

Video showing the raw clay preparation process in Japan circa 1955.

Samples of Laguna commercial clay bodies with a wide range of colors & properties.

Clay Bodies and Their Components

A clay body is simply a recipe or blend of raw materials formulated for specific firing temperatures and working properties (like plasticity, color, and shrinkage). In recipes you’ll see on Glazy, you’ll encounter three main ingredients over and over again:

- Clay: This is the primary clay component, providing the foundational structure and plasticity. Kaolin is often used for porcelain bodies because it’s very pure (white color, low impurities). Ball clay is sometimes added for extra plasticity.

- Feldspar: Feldspar acts as a flux, meaning it helps lower the melting point of the silica and other minerals in the clay body. It promotes vitrification (turning clay into a more glass-like, non-porous material) at the desired firing temperature.

- Silica (Flint): Silica is the glass-former. It’s what ultimately fuses during firing to create a tight, durable ceramic matrix.

Beyond these basic components, other materials can be added to fine-tune clay bodies. Grog (pre-fired, crushed clay) and sand reduce shrinkage and add texture. Fireclay provides high-temperature strength, while plasticizers like bentonite and Veegum improve workability. Talc helps control thermal expansion, particularly in low-fire bodies. Stains can be added to produce colorful results. These additives let ceramicists adjust their clay’s working properties and firing characteristics to suit specific needs.

Clay Properties

Choosing and understanding the right clay is one of the biggest factors in successful ceramics. Plasticity, shrinkage, absorption, and vitrification are central to how a clay behaves.

Plasticity & Workability

- Plasticity is the clay’s ability to be shaped without cracking and to maintain that shape once formed. Smaller, plate-like particles (like ball clay) increase plasticity, while larger, blocky particles (like pure kaolin) reduce it.

- Workability encompasses not just plasticity but also how a clay feels in the hands (sticky, stiff, gritty) and how easily it responds to forming techniques (wheel-throwing, hand-building, etc.).

- A highly plastic clay can be stretched and formed into very thin shapes or tall forms. However, it typically shrinks more, raising the risk of cracks. Clays with extra grog or sand have lower plasticity but can be easier for hand-building large items because they’re more stable and less prone to warping.

Roll a coil, bend it gently into a ring. If it cracks, the clay is short (low plasticity). If it bends smoothly without cracking, it’s quite plastic. This photo shows a very plastic commercial porcelain body.

Shrinkage & Drying

- All clays shrink from wet to dry (water evaporates) and again during firing (particles fuse). Total shrinkage often runs from ~10% to 15% or more, depending on the clay. Porcelains can shrink even more, sometimes up to 20%.

- Uneven drying can create stress and lead to cracks or warping, especially in high-shrinkage bodies. Drying your pieces slowly and evenly by covering them loosely and avoiding extreme drafts helps mitigate problems.

Absorption (Porosity)

- Absorption measures how much water a fired clay can soak up, reflecting how “sealed” or porous it is.

- Earthenware might have 10% or more absorption (quite porous), while stoneware typically falls between 0.5%-5%. Porcelain can be below 0.5%, effectively vitrified.

- For functional ware meant to hold food or liquids, low absorption (ideally under ~2%) is important to prevent leaking or bacteria growth. Earthenware remains porous and usually needs a well-fitting glaze to hold water, whereas a fully vitrified stoneware or porcelain does not strictly require a glaze to be waterproof.

Vitrification

- Vitrification is the process where clay fuses into a glassy, non-porous state at high temperature.

- Each clay body has a “maturing” range, the temperature where it becomes sufficiently vitrified without warping or melting. Stoneware and porcelain can be fired to true vitrification, while earthenware remains only partially vitrified (hence more porous).

- The level of vitrification affects strength, absorption, and durability. Over-firing a clay can cause bloating or slumping; under-firing leaves it weak and absorbent.

Firing Temperature & Thermal Expansion

- Firing Temperature: Different clays have different maturing points: earthenware at lower temps, stoneware/porcelain at higher. Firing outside a clay’s specified range leads to weak or distorted results.

- Thermal Expansion: The rate at which clay (and glaze) expands or contracts with temperature changes can cause crazing or shivering if there’s a mismatch. Some bodies are formulated to minimize thermal shock; others focus on maximum density and strength.

Selecting the Right Clay Body

Your choice of clay depends on what you’re making and how you plan to fire:

-

Functional Tableware (Mugs, Plates, Bowls)

- Stoneware or porcelain is preferred for low absorption and durability. Aim for a clay that reaches maturity (0–2% absorption) at your firing temperature (e.g., cone 6 stoneware in a cone 6 kiln).

- Earthenware can be used for decorative or less demanding functional pieces, but it remains porous unless fully sealed with glaze.

-

Hand-Built Sculpture or Large Forms

- A body with added grog or sand (often labeled as “sculpture clay”) reduces shrinkage and cracking. High-fire stoneware with grog can be good if the piece must go outdoors (frost resistance). Earthenware is workable for indoor pieces or if you only have a low-fire kiln.

-

Delicate, Translucent Work

- Porcelain is unbeatable for elegance and translucency but can be more finicky (higher shrinkage and warping). If you want a white body but less fuss, a white stoneware might be a good compromise.

-

Classroom / Beginners

- Choose a medium-plasticity stoneware with some grog to ease forming and reduce failures. Cone 5–6 stoneware is widely available and versatile.

- If your kiln only goes to ~Cone 04, you’ll be using earthenware or “low-fire” clay bodies.

Example Recipe: “English” Porcelain

A simple body is the standard “English” porcelain recipe:

| Ingredient | % Amount |

|---|---|

| Kaolin | 50% |

| Feldspar | 25% |

| Silica | 25% |

In this formula:

- Kaolin provides structure & plasticity,

- Feldspar helps everything melt and fuse at the right temperature,

- Silica adds strength and density once fired.

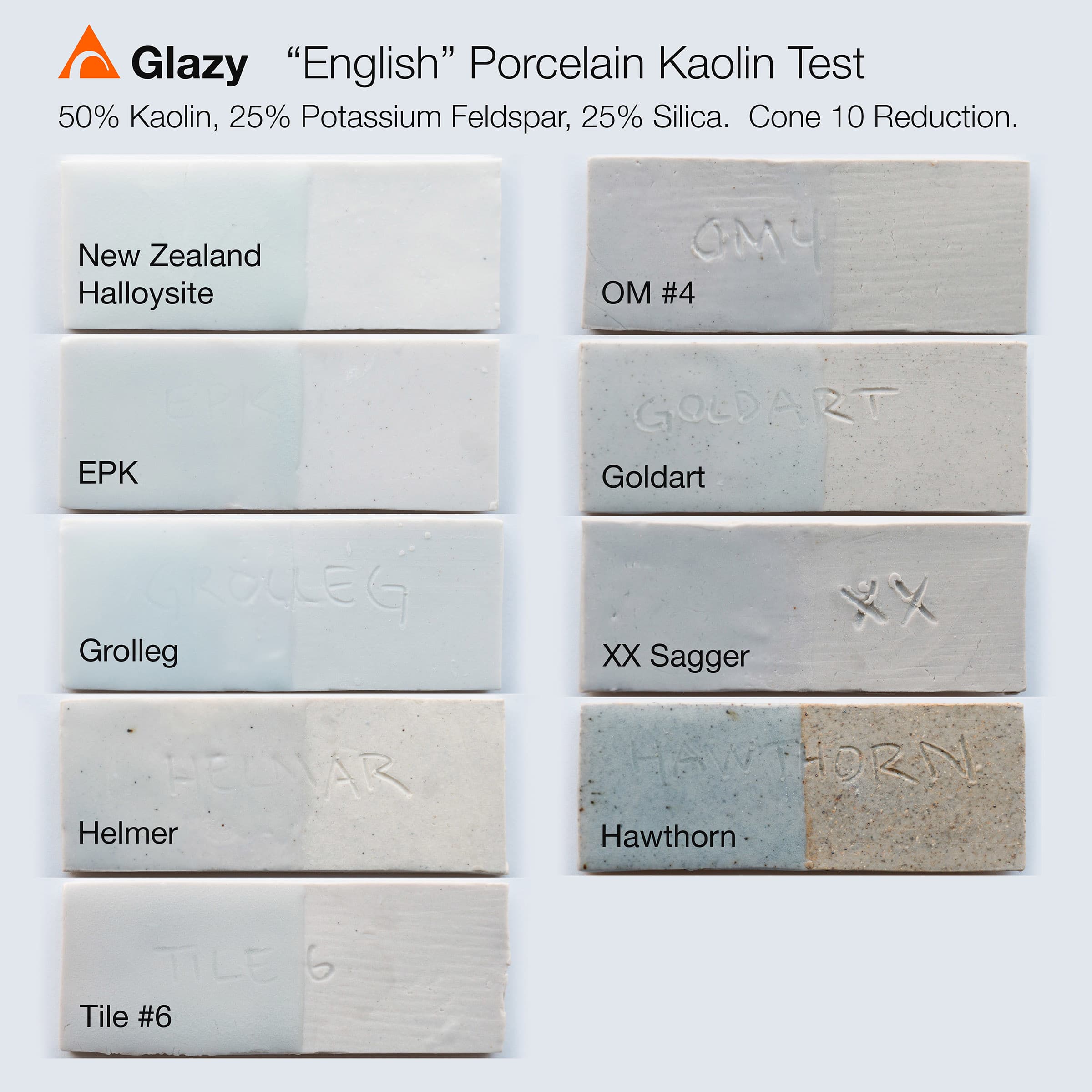

Here are 9 variations of the “English” porcelain recipe using various clays. Half of each test tile was glazed with Shaner Clear and the tests were fired to Orton cone 10 in reduction.

Glaze Fit Test

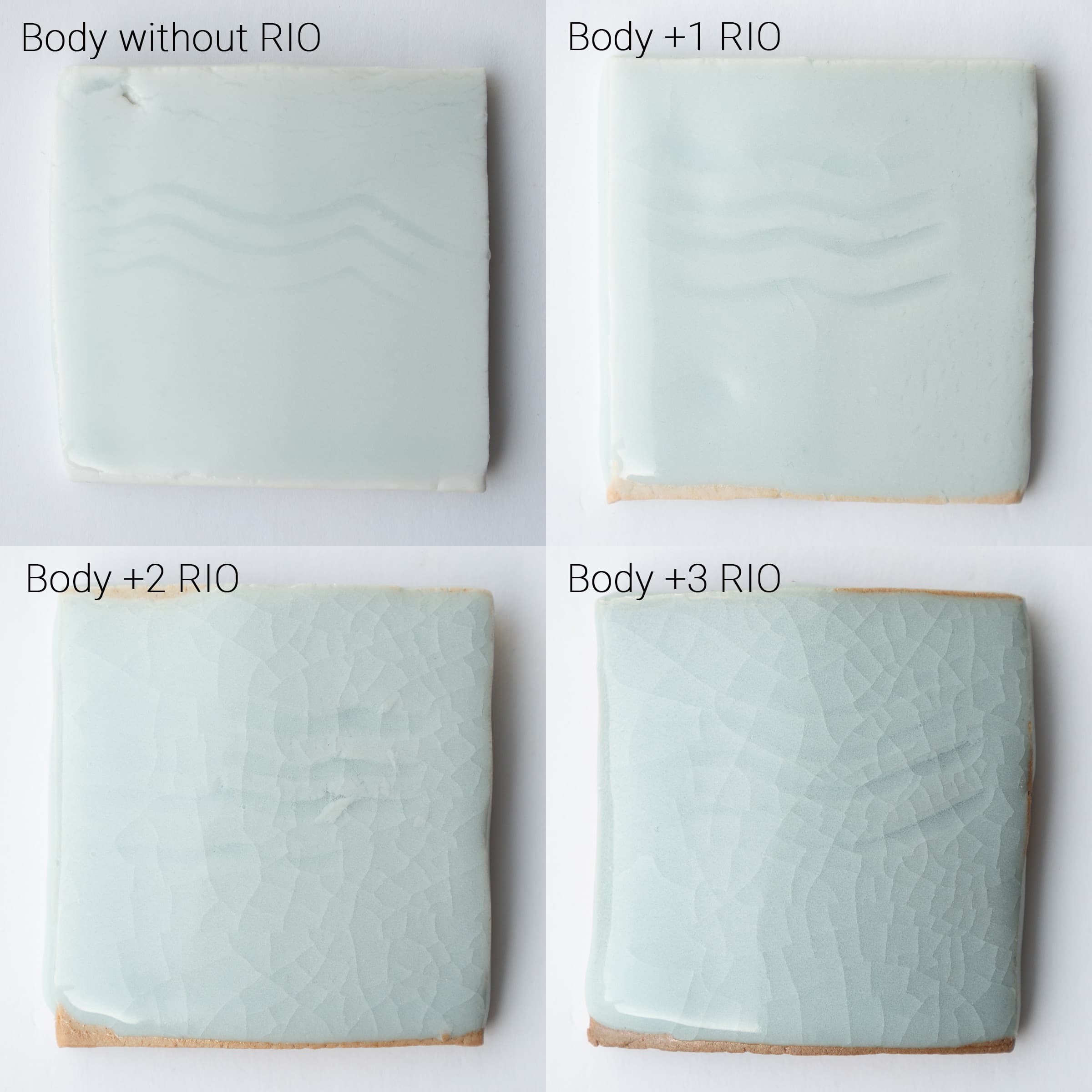

Here’s a test with a fixed glaze and variable body showing how the composition of the body can affect glaze fit. The glaze is Pinnell Blue Celadon (a fairly low-expansion glaze that does not usually craze on porcelain bodies), while the porcelain is a typical high-fire body with Red Iron Oxide (RIO) successively added in 1% increments. Fired in a reducing atmosphere to Orton cone 10. Without RIO, this glaze fits the body perfectly. After adding just 1% RIO to the body we can already see slight crazing, while at +2% RIO the glaze is completely crazed.

Colored Clay Bodies

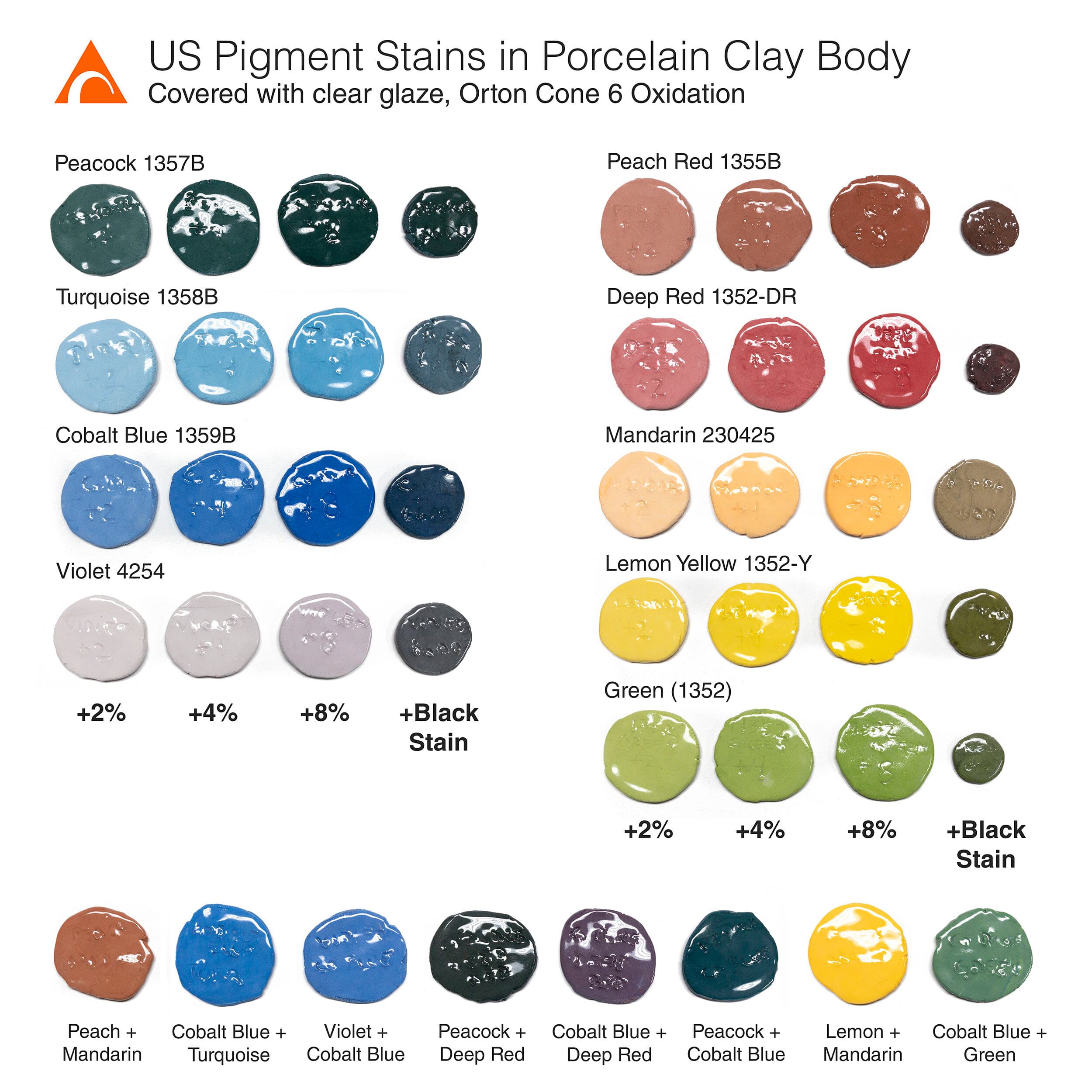

Each of these tests of US Pigment Stains was mixed with 100g porcelain clay body in amounts of +2%, +4%, +8%. The +8% was also mixed with black stain (Mason 6600, mixed about 25% black and 75% color). Link to porcelain clay body , Link to glaze

References

- Wikipedia: Clay , Earthenware , Stoneware , Porcelain

- Techno File: Clay Body Building