Major Oxides in Glazes

When you mix a glaze, you’re combining several powdered materials, each of which contributes certain oxides to the final melt. These oxides determine how easily the glaze melts, how fluid or matte it becomes, and how it ultimately looks and behaves on your fired pieces.

Traditional studio potters often talk about glaze ingredients as glass-formers, fluxes, and stabilizers. From a materials-science standpoint, though, you’ll often see these same oxides labeled as network formers, network modifiers, and network intermediates (or amphoteric oxides). The chart below shows how these categories roughly map to each other:

| Traditional Potter’s Term | ceramic science Term | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Glass-Former | Network Former | SiO₂, B₂O₃, P₂O₅ |

| Flux | Network Modifier | Na₂O, K₂O, Li₂O, CaO, MgO, etc. |

| Stabilizer | Network Intermediate | Al₂O₃, ZnO, TiO₂, ZrO₂ |

Despite these differences, the potter’s view is still a handy way to think of glaze design. Just remember that some oxides (like B₂O₃) are technically network formers but also serve a strong fluxing role at lower temperatures.

The Three Essential Oxide Groups

In the previous section What is Glaze?, we introduced three primary oxide groups:

- Glass Former (Silica / SiO₂) Essentially the backbone of all glazes.

- Fluxes (e.g., Na₂O, K₂O, CaO, MgO, B₂O₃) Fluxes lower silica’s melting point and can radically change color, surface finish, and thermal expansion.

- Stabilizer (Alumina / Al₂O₃) Alumina raises viscosity, prevents the glaze from running off your pot, and adds durability.

Yet in practice, most raw materials supply more than one oxide. For example, feldspar contributes silica, alumina, and fluxes all at once. Let’s look at each major oxide (or oxide family) to see how it shapes a glaze and which raw materials commonly provide it.

Silica (SiO₂): The Glass-Former

Silica is the primary glass-former. Without it, you wouldn’t get that hard, glassy surface. Pure silica melts only at extremely high temperatures (above 3100°F / 1700°C). To make it melt in typical ceramic kilns (cone 06–10), potters rely on fluxes (network modifiers).

A glaze high in silica is generally more scratch-resistant and durable. It also tends to have a lower thermal expansion, which can help reduce crazing.

Common Sources of Silica

Many glaze materials can provide SiO₂. Some sources are almost pure silica, while others are silicate minerals that contain silica combined with other oxides.

- Quartz (aka Flint or Silica): Ground silica that’s nearly pure SiO₂.

- Feldspar: Though often considered a flux source, feldspar contains a significant portion of silica as well as alumina.

- Clay (Kaolin , Ball Clay ): Clay itself is an alumino-silicate, meaning it provides both silica and alumina.

- Wollastonite (CaSiO₃): Primarily used for its calcium (flux) content, but also adds silica.

Alumina (Al₂O₃): The Stabilizer

Alumina boosts a glaze’s viscosity, helps it stay put on the pot, and improves durability. Though it’s often called a stabilizer by potters, in ceramic science terms it’s typically an “intermediate” that can participate in the glass network. If you add too little alumina, your glaze may run; too much can stiffen the melt into a matte.

Common Sources of Alumina

- Kaolin (China Clay): A very pure clay (Al₂O₃·2SiO₂·2H₂O) that supplies alumina and silica. Kaolin is an ideal source of alumina for glazes and is often added specifically to increase Al₂O₃ content.

- Ball Clay: Similar to kaolin but with more impurities and slightly higher plasticity. It can also help with suspension of the glaze slurry.

- Feldspar: Contains moderate alumina along with silica and alkali fluxes. For example, potash feldspar is roughly 18% Al₂O₃.

- Alumina Hydrate (Al(OH)₃): A direct, refined source of Al₂O₃, though it’s refractory and doesn’t melt easily, so it’s not as readily dissolved into the glaze as clay or feldspar and thus rarely used as a primary source of alumina.

The alumina in kaolin or ball clay also helps keep the powder glaze from shrinking or cracking as it dries on your bisque. It’s one reason most glaze recipes include at least a small percentage of clay.

Fluxes: Lowering the Melting Point

Flux is the collective term for oxides that reduce the melting point of silica, making it molten at normal firing ranges. Without fluxes, we would need extremely high temperatures to melt a glaze. Fluxes are also known as “network modifiers.”

Temperature Thresholds for Flux Behavior

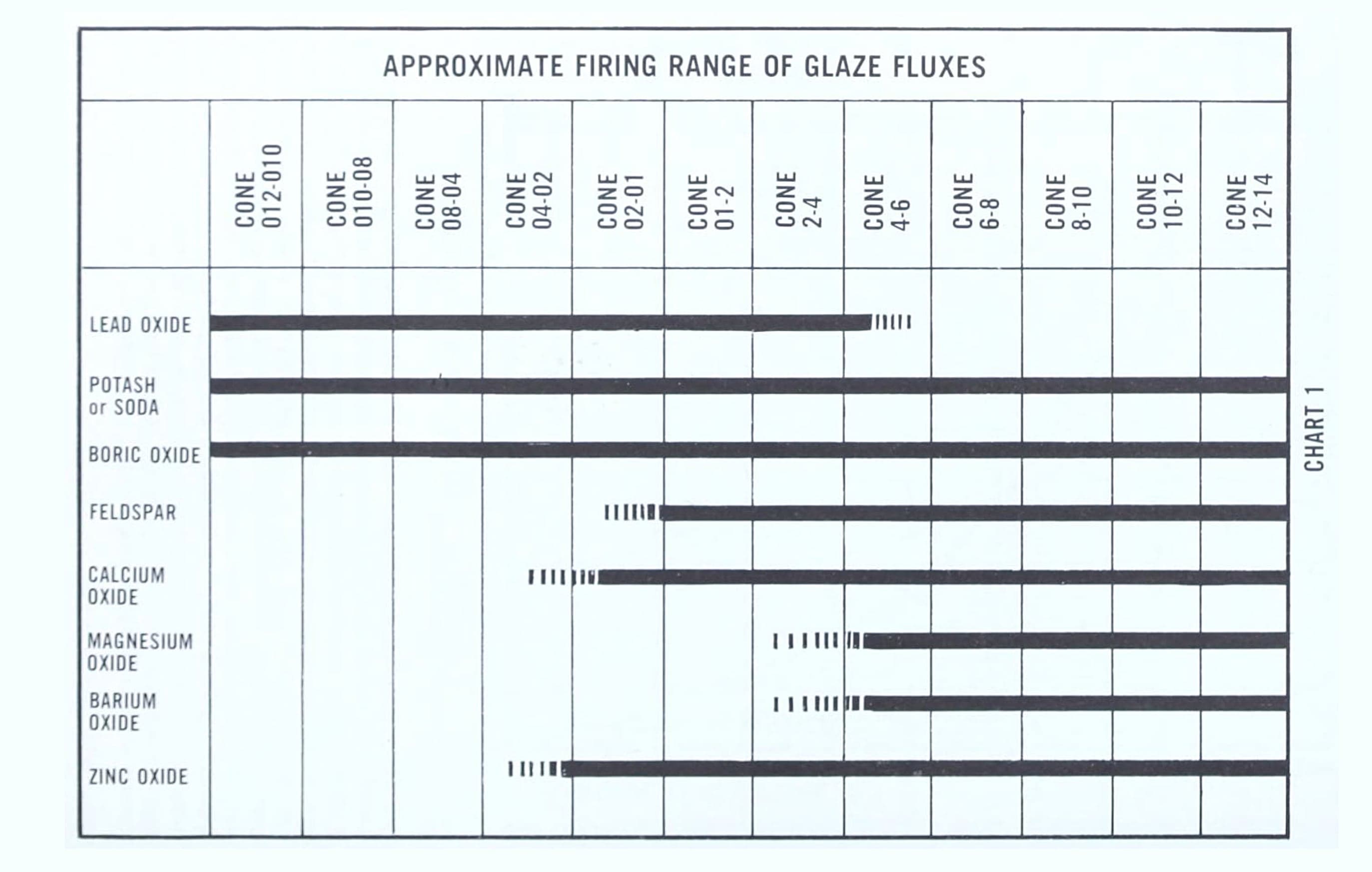

A key idea from ceramic science is that not all fluxes work equally well at all temperatures. For instance:

- Alkali metal oxides (Na₂O, K₂O, Li₂O) help from low-fire up through cone 10.

- Alkaline earths (CaO, MgO, BaO, SrO) need more heat to truly flux, often around cone 1-2 or higher. At low-fire, they may do very little unless paired with boron or alkalis.

- Boron (B₂O₃) fluxes over a broad range but is actually a network former in technical terms.

- Zinc (ZnO) can help from mid-fire onward; at lower temps or in reduction, it’s either ineffective or volatile.

Chart 1, page 165, “Approximate Firing Range of Glaze Fluxes” from “Clay and glazes for the potter” by Daniel Rhodes

Alkaline Fluxes (Na₂O, K₂O, Li₂O)

The alkali metal oxides, potassium oxide (K₂O), sodium oxide (Na₂O), and lithium oxide (Li₂O), are among the most active fluxes in ceramic glazes. They become effective at relatively low temperatures (from cone 06 up through mid/high fire) and drastically lower the melting point of the mix. In general, they’re known for producing very fluid melts and for creating glossy, transparent glazes. However, they also tend to raise glaze expansion, so high levels can cause crazing. Each alkali oxide behaves a bit differently, as outlined below.

Sodium Oxide (Na₂O)

Sodium is a strong flux especially effective at low to mid-fire temperatures. It produces very fluid melts, often resulting in glossy surfaces, but has relatively high thermal expansion. A glaze rich in Na₂O has a greater tendency to craze.

Common Sources

- Soda Feldspar (e.g., Minspar 200 ): Typically contains higher Na₂O relative to K₂O.

- Nepheline Syenite (e.g., A-270 ): A sodium-potassium rock with a higher overall flux content than feldspar, melting at lower temperatures.

- Soda Ash (Sodium Carbonate): Used in soda firing or occasionally added to glazes (though it’s highly soluble, so it’s not typical for stored glazes).

- Borate Frits: Many commercial frits incorporate Na₂O alongside boron to facilitate low-temperature melting.

Potassium Oxide (K₂O)

Potassium is another strong alkali flux that often yields bright, glossy glazes and can enhance color development. It also leads to high glaze expansion. It can promote crazing if used in excess, although to a lesser extent than sodium.

Common Sources

- Potash Feldspar (e.g., Custer Feldspar , G-200 Feldspar ): Real-world materials often contain a mix of K₂O and Na₂O, but with a higher proportion of K₂O.

- Nepheline Syenite (e.g., A-270 ): Also contains both Na₂O and K₂O but is favored for its lower melting range.

- Potassium Carbonate (Pearl Ash): Occasionally used in specialized or historical recipes and in salt or soda firing contexts.

Lithium Oxide (Li₂O)

Lithium is among the most powerful fluxes, capable of lowering the melting point even at small percentages. It has low thermal expansion compared to sodium and potassium and can help reduce crazing if used judiciously. Lithium can promote unique surface effects, including certain matte or crystalline textures, particularly at higher Li₂O levels. It can sometimes cause slight slurry-thickening issues in the bucket (especially lithium carbonate) and is more expensive than sodium/potassium sources.

Common Sources

- Lithium Carbonate: Dissolves easily in the glaze melt, though care is needed when mixing (it’s somewhat soluble in water).

- Spodumene and Petalite: Lithium aluminosilicate minerals, commonly used in stoneware and porcelain glazes for cone 6–10.

- Some Borate Frits: May incorporate lithium in addition to boron.

Key Takeaway All three oxides (Na₂O, K₂O, Li₂O) create highly fluid, often brightly colored glazes but can raise expansion and risk crazing. Lithium stands out for its comparatively low expansion, potential for special crystal/matte effects, and higher cost.

Alkaline Earth Fluxes (CaO, MgO, BaO, SrO) & ZnO

The alkaline earths calcium (CaO), magnesium (MgO), barium (BaO), strontium (SrO) plus zinc (ZnO) also act as fluxes but generally behave differently from the alkali metals. They typically melt at higher temperatures (most effective in cone 5–10 ranges) and form stiffer melts. Many alkaline earth–rich glazes develop satin or matte finishes if crystals grow upon cooling. Collectively, they contribute a lower thermal expansion than alkali oxides, which helps reduce crazing.

Calcium Oxide (CaO)

Calcium is a very common high-fire flux that promotes a durable, hard glass. Moderate amounts of CaO usually yield glossy surfaces; higher levels can promote matte or crystalline textures (calcium mattes). Calcium tends to lower glaze expansion relative to sodium/potassium fluxes, helping to reduce crazing.

Common Sources

- Whiting (Calcium Carbonate, CaCO₃): Decomposes during firing, releasing CaO.

- Wollastonite (CaSiO₃): Supplies both CaO and SiO₂, often helping glaze fit.

- Bone Ash (Calcium Phosphate): Also introduces some phosphate (P₂O₅).

Magnesium Oxide (MgO)

Magnesium is another high-temperature flux; melts less readily than CaO but imparts characteristic silky matte surfaces when present in sufficient quantity. It commonly yields buttery or waxy matte glazes (especially in slow-cool firings) and has an especially low thermal expansion, making it useful for combating crazing. (See “Magnesium Matte” .)

Common Sources

- Dolomite (CaCO₃·MgCO₃): Provides both MgO and CaO upon decomposition.

- Talc (Mg₃Si₄O₁₀(OH)₂): Often used in low-fire glazes and clay bodies to supply MgO and silica.

- Light Magnesium Carbonate (MgCO₃): A pure source of MgO that decomposes during firing. Very light and fluffy in texture, often used in crawling glazes.

Barium Oxide (BaO)

Toxic in raw form; high-barium glazes can leach and are generally not food-safe.

Barium is valued for creating unique mattes and certain color responses. It’s considered somewhat refractory and can help produce subtle crystal growth upon cooling.

Common Sources

- Barium Carbonate (BaCO₃): The principal raw source for BaO. However, it is toxic, so many potters substitute strontium where possible.

Strontium Oxide (SrO)

Strontium behaves similarly to barium (matte finishes, interesting color modifications) but is much less toxic. Due to this, it is often used as a barium substitute for safer functional ware, though exact 1:1 swaps may require slight formula adjustments. Strontium produces smooth satin-to-matte surfaces in mid/high-fire ranges.

Common Sources

- Strontium Carbonate (SrCO₃): Decomposes during firing to release SrO.

Zinc Oxide (ZnO)

While not an alkaline earth chemically, zinc often gets grouped here because it acts as a high-fire flux with some similar behaviors. Zinc acts as a mid/high-fire flux that can promote glossy surfaces. It also encourages the growth of zinc-silicate crystals in specialized crystalline glazes, producing dramatic crystal patterns. At high temperatures in reduction firings, zinc is volatile and may be lost, although it may still be effective as an early flux in the glaze melt.

Common Sources

- Zinc Oxide (ZnO) powder is typically added directly.

- Some frits may incorporate zinc in their formula.

Related Glaze Categories

Bristol , Specialty → Crawling

Key Takeaway Alkaline earths generally form stiffer melts, matte or satin finishes, and lower expansion (helping reduce crazing). Calcium often yields a hard, glossy surface, magnesium is known for silky mattes, barium/strontium produce specialized mattes, and zinc can foster unique crystalline effects in oxidation.

Lead Oxide (PbO)

Toxic; Once a common low-temperature flux in historical glazes, lead oxide is now avoided in most studio ceramics due to its toxicity and risk of leaching. Modern alternatives include boron-based fluxes and various alkali or alkaline earth combinations, making lead largely obsolete (and unsafe) in contemporary functional ceramics.

Final Thoughts on Flux Balance

Balancing alkaline and alkaline earth oxides (plus boron) is how potters tune melting temperature, surface, color response, and thermal expansion. Too much Na₂O or K₂O can push crazing or runniness; alkaline earths like CaO, MgO, or SrO stiffen the melt, create mattes, and lower expansion. Lithium can unlock special effects, and zinc can drive crystal growth if the glaze and firing support it.

All flux choices interact with colorants, so the journey of refining glazes often involves experimenting with various combinations of alkali/alkaline earth ratios to achieve the perfect melt, surface, and hue.

Boron (B₂O₃)

Boron is special: it’s a network former in ceramic science (like silica), but we usually treat it as a flux at earthenware and mid-fire. It drops melting temperature and broadens the firing range. Nearly all low-fire and many mid-fire glazes rely on boron, often from frits, colemanite, or Gerstley Borate.

Excessive B₂O₃ (above ~12% in some mixes) can reduce durability. Pinholes can show up if there’s too much boron and not enough heatwork to let the glaze smooth over.

Common Sources

- Borate Minerals: Traditionally, minerals like Colemanite (calcium borate) and ulexite (sodium calcium borate) were used in formulating glazes. These minerals release B₂O₃ (along with CaO/Na₂O and other oxides) when melted. Gerstley Borate is a popular raw material (a mix of colemanite and ulexite with clay) that was widely used in studio glazes as a source of B₂O₃ and CaO. However, raw borate minerals can be somewhat inconsistent and partially soluble in water.

- Boron Frits: Today, the most common source of boron in glazes is through frits – manufactured, pre-melted glasses that contain B₂O₃ and other oxides. For example, Ferro Frit 3134 , 3124 , 3195 , etc., are all boron frits commonly used in glazes. Frits have the advantage of being relatively insoluble and reliable. A frit labeled as a borate frit might contain B₂O₃ along with fluxes like CaO, Na₂O, etc., as well as other oxides.

- Boric Acid / Borax: In some cases, boric acid (H₃BO₃) or borax (sodium borate) is used, especially in specialty raku or low-fire glaze formulas. These are highly soluble in water, so they’re not ideal for stored glaze mixtures, but they do provide B₂O₃ and alkali flux if used fresh.

Other Oxides

While colorants aren’t part of the main glaze skeleton, they can change both look and behavior, sometimes acting as secondary fluxes.

Iron Oxide (Fe₂O₃)

Iron oxide is a colorant and, under certain conditions, a flux. In oxidation (electric kiln), it yields browns, tans, and reds and stays fairly refractory. In reduction (gas/wood), it shifts to FeO, a strong flux, giving fluid, deep glazes like tenmoku (black/brown) and celadon (blue-green). High iron can foster crystal growth in iron-reds and mattes.

Common Sources

- Red Iron Oxide (Ferric Oxide): ~95%+ Fe₂O₃, very consistent and pure, especially synthetic varieties, the most common way to source iron.

- Spanish Red Iron Oxide: a brown red natural earth based on hematite deposits in Spain containing 85% iron oxide.

- Yellow Iron Oxide: A hydrated form that calcines to red iron when fired. This is not the same as yellow ochre, which is a naturally-occurring impure mixture of yellow iron oxide, clay, etc.

- Yellow Ochre: Soft and crumbly, often contaminated with clay, limestone, and other matter.

- Black Iron Oxide (Magnetite): Contains iron in a more reduced state; can melt more easily and is often used for speckling or strong coloration.

- Iron-Bearing Clays/Slips: Natural clays (like terra cotta) or high-iron slips (e.g.,Alberta Slip , Redart ) that supply iron (and other oxides) for unique glaze effects.

- Misc. Iron Compounds: Materials like Crocus Martis or Iron Chromate , though less commonly used in standard recipes.

Related Glaze Categories

Iron , Iron → Celadon , Iron → Celadon → Blue , Iron → Celadon → Green , Iron → Celadon → Yellow , Iron → Celadon → Chun , Iron → Amber , Iron → Tenmoku , Iron → Tea Dust , Iron → Tessha, Hare’s Fur , Iron → Kaki, Tomato Red , Iron → Oil Spot , Iron → Slip-Based , Yellow → Iron

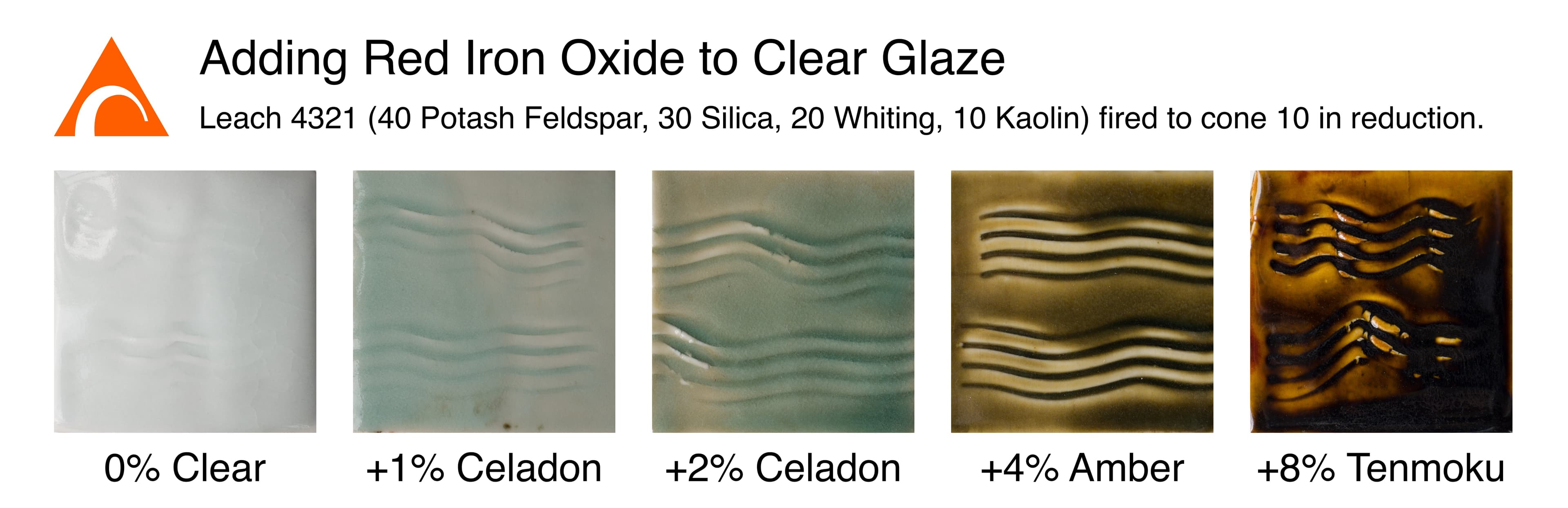

Here we see a line blend adding red iron oxide to a clear base glaze (Leach 4321 ).

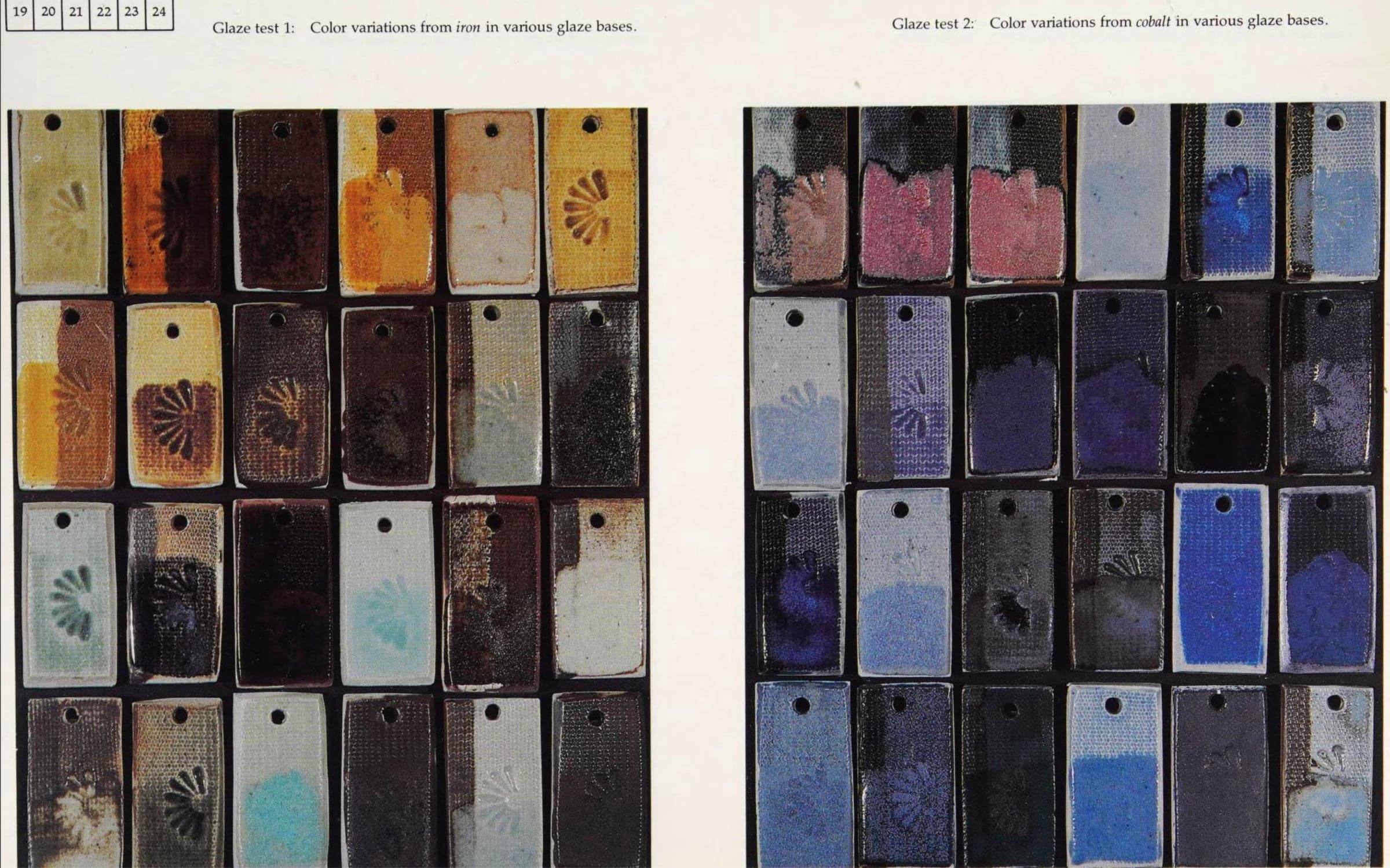

Color variations from iron (left) and cobalt (right) in various glazes from The Ceramic Spectrum : A Simplified Approach to Glaze & Color development by Robin Hopper, page 49. Hopper shows how not only the amount of colorant but also the glaze composition can affect the final color.

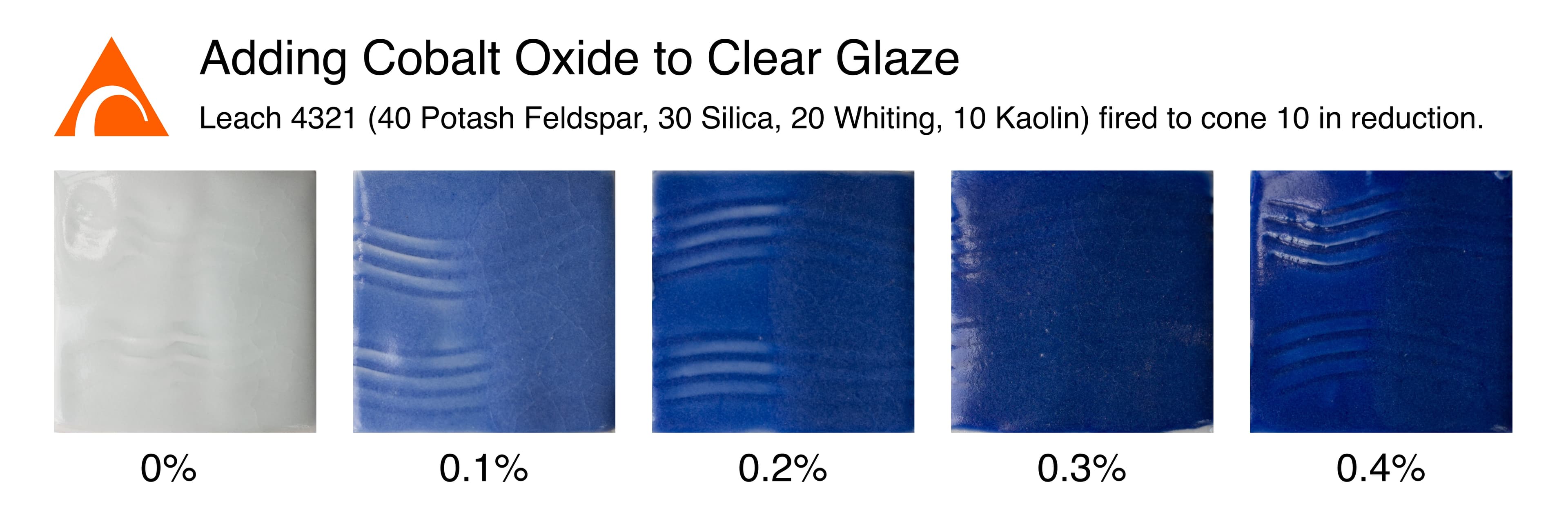

Cobalt (CoO / Co₃O₄)

A potent, reliable blue colorant for both oxidation and reduction. Even tiny additions (0.1–1%) can yield intense blues. Excess cobalt can result in dark blue-black glazes or surface defects.

Common Sources

- Cobalt Oxide: A strong black powder.

- Cobalt Carbonate: A lavender powder that decomposes to CoO in firing.

Related Glaze Categories

Cobalt has been used in ceramics throughout history. Left: Cobalt glazed Tankard, Iran, 1180-1220 Right: Jar with cobalt decoration, China, early 15th century

Here we see a line blend adding cobalt to a clear base glaze (Leach 4321 ). Note that cobalt is a powerful colorant, and only 0.1% (not 1%!) is needed to make a blue glaze.

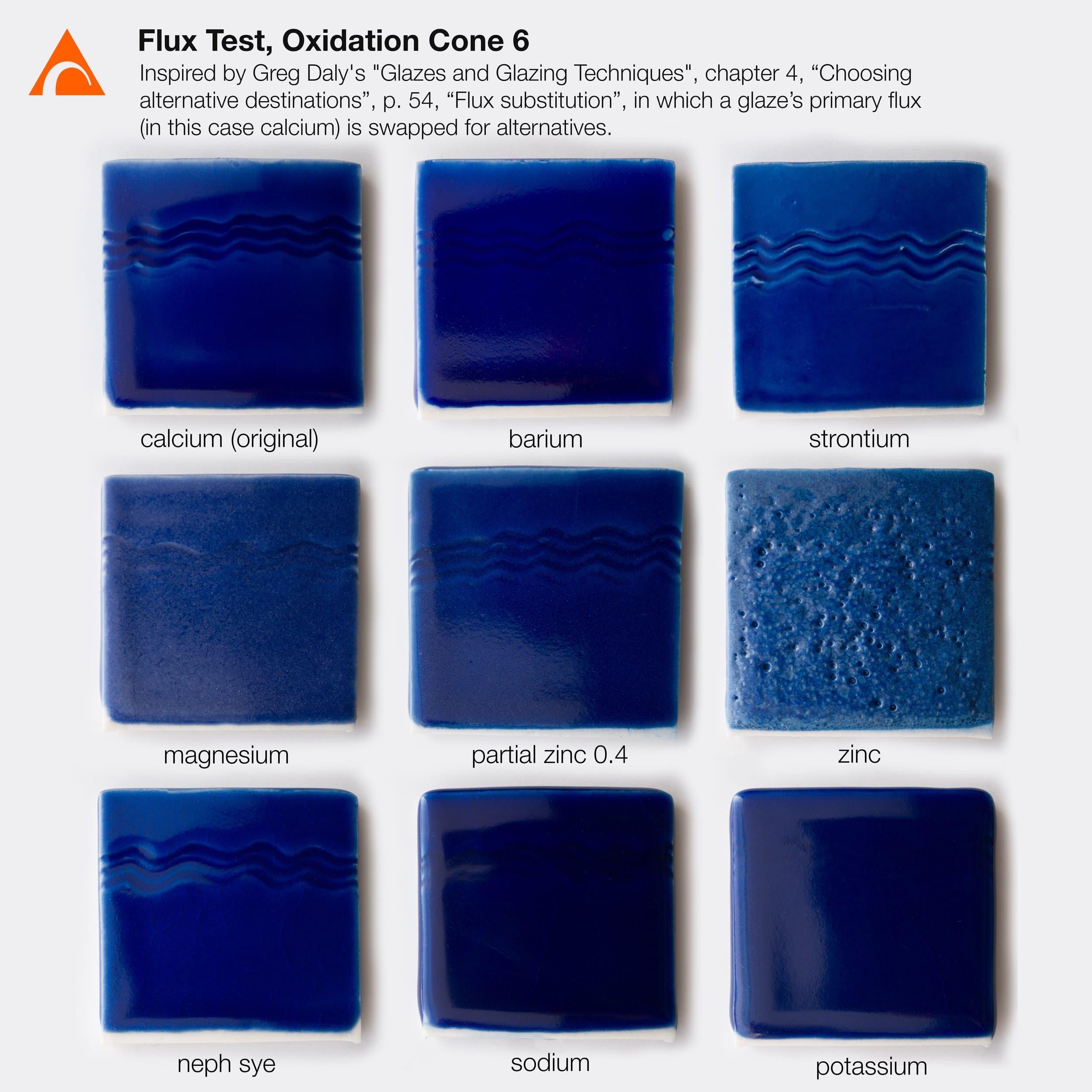

This flux test was inspired by Greg Daly’s “Glazes and Glazing Techniques” , chapter 4, “Choosing alternative destinations”, p. 54, “Flux substitution”, in which a glaze’s primary flux (in this case calcium) is swapped for alternatives. As a typical example, in a calcium-fluxed glaze you can replace all of the CaO with zinc, barium, magnesium, strontium, or sodium/potassium. In this example, I’ve replaced the calcium with magnesium. All of the flux tests can be found in this Glazy collection: Flux Test

Copper (CuO / Cu₂O)

Produces greens, turquoise, and blues in oxidation and the classic copper reds (oxblood) in reduction. Some bases or firings yield turquoise or metallic effects. Higher amounts may make glazes more fluid and increase leaching risk if the base isn’t stable.

Common Sources

- Copper Oxide (Black): CuO (black powder).

- Copper Oxide (Red): Cu₂O (red powder), reduced form of the black copper oxide (CuO).

- Copper Carbonate: A greenish powder that’s easier to disperse.

Related Glaze Categories

Red → Copper , Red → Copper → Oxblood , Red → Copper → Flambe , Red → Copper → Peach Bloom , Green → Copper , Green → Oribe , Turquoise , Blue (containing Copper)

Various forms of copper: Black Copper Oxide , Copper Carbonate , and Red Copper Oxide

Chromium (Cr₂O₃)

Typically yields green (often olive/forest tones). In certain bases, it can produce pink (chrome-tin pink), yellows, or browns. Chromium can fume at high temperatures, sometimes flashing nearby tin glazes pink.

Common Sources

- Chrome Oxide: A dull green powder used sparingly (1–2% or less).

Related Glaze Categories

Green → Chrome , Pink (including Chrome)

Manganese (MnO₂ / MnCO₃)

Examples of glazes with manganese. Top: Midnight Blue , Gold , Astor#23 Metallic Black , Glossy gray, blue and brown - Lasse Östman Bottom: Shadow , Speckled Sand , Metálico CMN2 , Argentum P

Gives browns, purples, or blackish tones depending on the base. Common for speckles (coarse granules). Can fume at high fire, leaving halos on nearby ware.

Common Sources

- Manganese Dioxide: Dark brown-black powder, can cause speckling if used in coarse form.

- Manganese Carbonate: Lighter tan powder, disperses more evenly for uniform color.

Related Glaze Categories

Purple → Manganese , Yellow → Manganese , Crystalline → Manganese

Nickel (NiO)

Usually gives greys or soft browns and modifies other colors (e.g., toning down cobalt). It’s relatively weak, requiring higher percentages for noticeable color shifts.

Common Sources

- Nickel Oxide: A gray-green powder.

- Nickel Carbonate: A pale green powder, less common but easier to disperse.

Related Glaze Categories

Green → Nickel , Blue → Nickel , Purple → Nickel , Yellow → Nickel

Titanium (TiO₂)

Titanium can opacify, crystallize and variegate glazes. Small additions of 1-2% dissolve with minimal effect, but above 2%, titanium creates translucent, silky opacity and mottling through micro-crystal formation. At 4-6%, it brightens colors while creating variegation, and at high amounts (10%+), produces matte, textured surfaces with visible crystallization.

Common Sources

- Rutile : A natural TiO₂ mineral containing iron, creates warm tones and variegated effects.

- Titanium Dioxide : Pure titanium dioxide is used when clean opacification is needed.

- Ilmenite : Ilmenite provides speckling effects.

Related Glaze Categories

Blue → Rutile Green → Titanium

Zirconium (ZrO₂)

Zirconium creates consistent, reliable opacity without variegation, producing dense, uniform whites and increasing both gloss and melt viscosity. It’s effective at both low and high temperatures, typically used at 8-12% for full opacity.

Common Sources

Tin Oxide (SnO₂)

A classic opacifier historically used in majolica and other white glazes. Tin oxide produces a softer, milkier white than zircon. It also interacts with chrome to form pink hues. In recent years, tin oxide has become very expensive, and many opt for the cheaper zirconium silicates for opacifying effects.

Phosphorus (P₂O₅)

Phosphorus is a network former in ceramic chemistry, much like silica (SiO₂) and boron (B₂O₃). In practice, it usually enters a glaze through bone ash (calcium phosphate) or, to a lesser extent, natural wood ash, and most formulations keep it below about five percent. Though overshadowed by silica, even small amounts of phosphorus can influence a glaze’s overall character, encouraging subtle crystal growth that may yield soft mattes or milky, opalescent surfaces. Phosphates also tend to shift or soften colors, lending pastel or variegated effects that can be hard to achieve with other oxides.

Beyond aesthetics, phosphorus plays a notable role in specialized or “synthetic ash” glazes, where adding bone ash provides both a fluxing component (calcium) and phosphate in one material. This combination can mimic natural ash effects, like complex runs and variegation, without requiring a wood-kiln firing. While not a staple in every studio recipe, phosphorus offers potters a nuanced way to explore new textures, color breaks, and surface qualities when used thoughtfully.

Common Sources

- Bone Ash (Calcium Phosphate) – The primary source, typically used at 1–5%.

- Wood Ash – Contains smaller amounts of P₂O₅, varying by the wood species and burning process.

Related Glaze Categories

Ceramic stains (Mason stains, etc.) are another option for color, created by pre-firing and stabilizing these metal oxides (and others). They offer more predictable hues than raw oxides alone.

Putting It All Together

When you read a glaze recipe, something like:

- 40% Feldspar

- 30% Silica

- 20% Whiting

- 10% Kaolin

- +2% Red Iron Oxide (as colorant)

you’re essentially mixing up a balance of oxides:

- Feldspar brings sodium/potassium fluxes, plus some silica and alumina.

- Silica (Flint) is your main glass-former.

- Whiting supplies calcium flux.

- Kaolin adds alumina (and some silica) to stabilize the melt.

- Iron Oxide modifies color and, under reduction, can become a strong flux.

During firing, the fluxes break down and help silica melt, alumina keeps the melt from running, and the colorant, iron, changes the color of the glaze depending on atmosphere (oxidation vs. reduction). Each oxide’s proportion directly affects melt temperature, surface texture (matte vs. gloss), color, and thermal expansion.

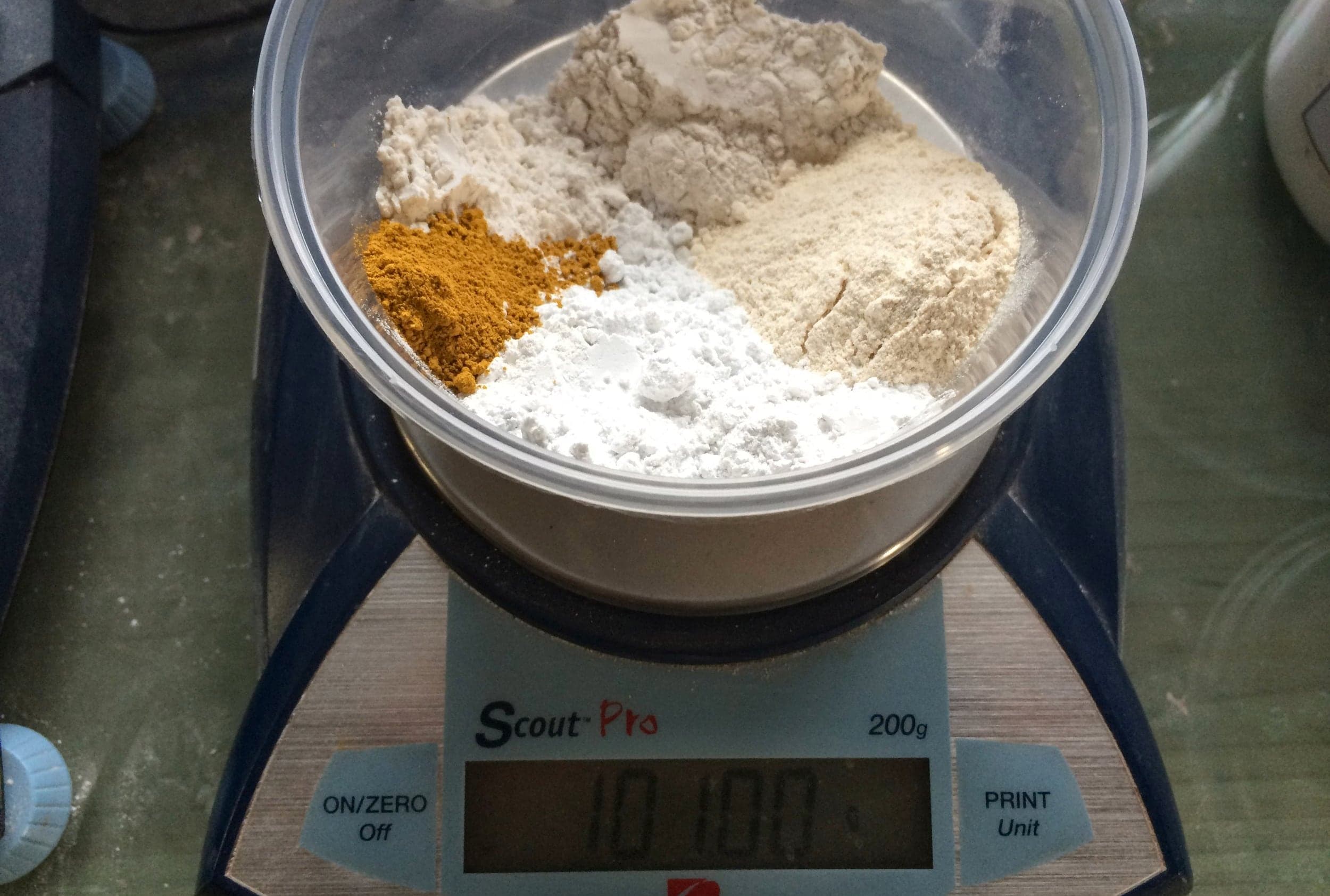

Measuring out a test batch of glaze with contemporary materials including feldspar, silica, whiting, kaolin, and an additional 1% yellow iron oxide.